Since I've been on a mini Christopher Hitchens kick, try his brutal trashing of George Tenet: "A Loser's History: George Tenet's Sniveling, Self-Justifying Book Is a Disgrace".

History (Mostly Antebellum America), Law, Music (from Classical to Frank Zappa -- are they the same?) and More

Pages

▼

Monday, April 30, 2007

Sunday, April 29, 2007

The Fillmore Rangers

Poor Millard Fillmore! During the 1848 presidential campaign, Louisiana Democrats apparently figured out that it wouldn't be all the credible to attack the pro-slavery credentials of Zachary Taylor -- after all the general owned one hundred slaves. They therefore went after Millard:

John M. Sacher, A Perfect War of Politics: Parties, Politicians and Democracy in Louisiana, 1824-1861 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press 2003), at 150-51.

On the other hand, Millard did have a fan club. Whig enthusiasts formed a club called the "Fillmore Rangers," "whose 'appearance, songs, shouts, music, & banners kill[ed] off the charge of abolition.'" Id. at 153.

The Fillmore Rangers were apparently effective. Millard (together with his running mate) received 54.6 percent of the vote in Louisiana.

Shortly after the election, a grateful Millard graciously acknowledged the Rangers' heroic efforts on his behalf:

The [Louisiana] Democrats concentrated their venom on Whig vice presidential candidate Millard Fillmore. Arguing that northern Whigs were antagonistic to slavery and had voted in favor of the Wilmot Proviso, Democrats reminded voters that they could not vote for Taylor without voting for the "avowed and notorious abolitionist" Fillmore. Democratic orators denied they slandered Fillmore with this designation because they claimed to possess evidence that Fillmore had proudly called himself an abolitionist.

John M. Sacher, A Perfect War of Politics: Parties, Politicians and Democracy in Louisiana, 1824-1861 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press 2003), at 150-51.

On the other hand, Millard did have a fan club. Whig enthusiasts formed a club called the "Fillmore Rangers," "whose 'appearance, songs, shouts, music, & banners kill[ed] off the charge of abolition.'" Id. at 153.

The Fillmore Rangers were apparently effective. Millard (together with his running mate) received 54.6 percent of the vote in Louisiana.

Shortly after the election, a grateful Millard graciously acknowledged the Rangers' heroic efforts on his behalf:

I am honored by the receipt of your note the 21st ult. [i.e., October 21, 1848], enclosing a copy of the address of the "Fillmore Rangers" of New Orleans.

It did not reach me until the contest had closed, and the din of strife had given way to the exultations of triumph and the song of victory.

But I can assure you that the noble and truly national sentiments of that address find a hearty response in my breast, and the triumphant Whig vote in your city is the best evidence of the zeal and ability with which the young men of your club discharge their duty to the Whig party and the country. My illustrious associate on the ticket required no vindication, and I therefore feel the more deeply the obligation which I have incurred by the noble stand which these young men took in my favor, and I acknowledge it with heartfelt thanks, and trust they will never have reason to regret the confidence they have reposed in me.

Please make my grateful acknowledgments to the Club over which you preside, and accept for yourself the assurance of my high regard and esteem.

Saturday, April 28, 2007

Outdoor Stereo

How about something different for a Saturday afternoon? Let's talk stereos.

Since it's warming up a bit here in lovely NW NJ, I've taken my summer/oudoors system out of hibernation.

They say there are two kinds of stereo guys: amplifier guys and speaker guys. In my heart, I tend toward the former. The guts of the system are a tube amp and preamp:

Since it's warming up a bit here in lovely NW NJ, I've taken my summer/oudoors system out of hibernation.

They say there are two kinds of stereo guys: amplifier guys and speaker guys. In my heart, I tend toward the former. The guts of the system are a tube amp and preamp:

My favorite tube is the 300B, but at 8W, the 300B just won't cut it for outdoor use. This amp, an Assemblage ST-40, is a stereo amp that uses EL34 tubes hooked up in pentode and puts out probably 35W. It was the first amp I ever put together, made from a kit sold by a company called The Parts Connection, which was the parts-and-kits arm of the old Sonic Frontiers. Every time I plug this amp in, I'm amazed how good it sounds. I love it.

The preamp is a Foreplay clone, jazzed up with some tweaks and some "designer" parts, such as the caps. I've also added twin stepped attenuators, assembled from Welborne Labs kits. Very pricey, but I just hate potentiometers.

Finally, here are the speakers. They are based on Pi Speakers Tower 2 kits. The boxes are MDF, veneered in ash with cherry borders. Frankly, I'm not wild about the ash look, but it was worth experimenting. Whatever they look like, I know the boxes are well-made. There are two layers of MDF on the front faces, almost 1 1/2 inches worth, and they're well-braced inside. The Tower 2s mate extremely well with tube equipment.

Friday, April 27, 2007

David Halberstam R.I.P.

I understand the reluctance to speak ill of the dead. I enjoy and respect Michael Barone's writing. However, Mr. Barone's column on David Halberstam is very odd indeed.

I have previously noted that, in his book Triumph Forsaken, Mark Moyar characterizes Halberstam as having done "more harm to the interests of the United States than any other journalist in American history." Barone mentions the book and, by way of a sort of praeteritio, Moyar's negative view of Halberstam ("([Halberstam's] coverage [of Vietnam] has been attacked recently by historian Mark Moyar in Triumph Forsaken, a subject I'll leave for another day.)").

But how can you come to grips with Halberstam -- and Vietnam -- and the media's hyperventilating coverage of Iraq today -- without confronting the devastating case Mark Moyars makes?

I have previously noted that, in his book Triumph Forsaken, Mark Moyar characterizes Halberstam as having done "more harm to the interests of the United States than any other journalist in American history." Barone mentions the book and, by way of a sort of praeteritio, Moyar's negative view of Halberstam ("([Halberstam's] coverage [of Vietnam] has been attacked recently by historian Mark Moyar in Triumph Forsaken, a subject I'll leave for another day.)").

But how can you come to grips with Halberstam -- and Vietnam -- and the media's hyperventilating coverage of Iraq today -- without confronting the devastating case Mark Moyars makes?

Wednesday, April 25, 2007

The District of Columbia House Voting Rights Act of 2007

Last week, the House of Representatives passed the "District of Columbia House Voting Rights Act of 2007." Among other things, it would grant the District a voting representative in the House.

The proposed legislation is so obviously unconstitutional (see here and here) that it's incomprehensible to me that anyone could think otherwise. Are there serious (or even semi-serious) scholars who contend the legislation is constitutional? If so, who are they? And what do they cite?

The proposed legislation is so obviously unconstitutional (see here and here) that it's incomprehensible to me that anyone could think otherwise. Are there serious (or even semi-serious) scholars who contend the legislation is constitutional? If so, who are they? And what do they cite?

Tuesday, April 24, 2007

A Picture That Doesn't Suck -- And A Picture That Does

Harry called me Sunday evening and told me with some pride (although I don't think he's the father) that one of his cows had given birth to twins -- apparently a fairly uncommon event. Well, I rushed over and took a bunch of photos, all of which sucked, except for one. Here's the one that didn't suck:

Here, on the other hand, is one that did suck:

The Singular Plural

I've already told you about the Paul McCartney-inspired double preposition. Well, here's another grammatical trick with which to have fun with: the singular plural!

The singular plural is very easy. Just use the singular form for the plural. For some reason, it works particularly well with animals (no doubt due to the well-known "deer effect"): "Hey, guys, look at all the cow in that field over there!"

A more sophisticated variant occurs with the use of words with altered plural forms: "I've never seen so many mouse in my life!"

The singular plural is very easy. Just use the singular form for the plural. For some reason, it works particularly well with animals (no doubt due to the well-known "deer effect"): "Hey, guys, look at all the cow in that field over there!"

A more sophisticated variant occurs with the use of words with altered plural forms: "I've never seen so many mouse in my life!"

Sunday, April 22, 2007

The Bloody Tree of Liberty

Not sure whether this will work, but what the hey. It's a hilarious -- and depressing -- Penn & Teller anti-gun control video, but the real reason I'm posting it is that, consistent with today's theme, it begins with a famous Thomas Jefferson quote.

With Friends Like This . . .

Since I suddenly seem to be on a Thomas Jefferson kick . . .

Since I suddenly seem to be on a Thomas Jefferson kick . . .I'm not a big fan of Thomas Jefferson. In an effort to see the other side, I did some more reading about him last year. Unfortunately, one foray -- a book entitled The Wolf By the Ears: Thomas Jefferson and Slavery by John Chester Miller (New York: The Free Press 1977) -- proved somewhat counterproductive.

This otherwise admirable book contains a chapter about Sally Hemings that is utterly appalling. In a nutshell, the author violently denies that Jefferson could possibly have had sex and children with Sally Hemings. He reviews the source of the allegations, James Callender, and correctly pronounces him utterly untrustworthy. He then reviews the allegations themselves -- that Jefferson allegedly seduced a 16 year old girl; that he never acknowledged his alleged children, to the point that they did not even realize that Jefferson was his father; that he did not free them until his death; that he did not even free Sally Hemings in his will; etc., etc.

The author concludes that, if these allegations were true, Jefferson would be the lowest sort of scum and an utter hypocrite; that Jefferson was not the lowest sort of scum or an utter hypocrite, but rather quite the contrary; ergo, the allegations could not possibly be true. Q.E.D. As a corollary, he angrily brands Madison Hemings a liar for claiming that he was Jefferson's son (and/or Sally Hemings a liar, if she in fact told Madison that he was Jefferson's son). Without a shred of evidence, he pins guilt, if any, on the since-acquitted Carr brothers. He berates others (particularly Fawn Brodie) who had found the allegations plausible and makes clear that he deems them stupid at best and malevolent at worst.

Here's a taste (at 175-76, emphasis added):

If then he is to be accused of seducing a sixteen-year-old slave girl and having children by her whom he held as slaves, it is in utter defiance of the testimony he bore over the course of a long lifetime of the primacy of the moral sense and his loathing of racial mixture. . . How can his frequent assertions that his conscience was clear and that his enemies did him a cruel and wholly unmerited injustice be reconciled with the Jefferson of the Sally Hemings story? -- unless, of course, Jefferson is set down as a practitioner of pharisaical holiness who loved to preach to others what he himself did not practice?

If the answer . . . is that Jefferson was simply trying to cover up his illicit relations . . . he deserves to be regarded as one of the most profligate liars and consummate hypocrites ever to occupy the presidency. To give credence to the Sally Hemings story is, in effect, to question the authenticity of Jefferson's faith in freedom, the rights of man, and the innate controlling faculty of reason and the sense of right and wrong. It is to infer that there were no principles to which he was inviolably committed, that what he acclaimed as morality was no more than a rhetorical facade for self-indulgence, and that he was always prepared to make exceptions in his own case when it suited his purpose. In short, beneath his sanctimonious and sententious exterior lay a thoroughly adaptive and amoral public figure . . ..

Whoops!

I was going to write the author, a professor of history at Stanford, to ask what he had to say now that DNA testing has proved him so terribly wrong. Would he stand by his conclusions? Unfortunately, he died in 1991, so we'll never know his response.

More Hitchens

Since I just mentioned Christopher Hitchens's Jefferson biography, here are some thoughts I set down about the book while reading it:

Since I just mentioned Christopher Hitchens's Jefferson biography, here are some thoughts I set down about the book while reading it:It's certainly not the first biography of Jefferson you'd want to read -- it assumes a general knowledge of the man and events. If you don't know of him, Hitchens is a highly opinionated and highly controversial -- and highly amusing -- commentator (among other things, he wrote books savaging Mother Teresa and Bill Clinton), and it's fascinating to see what he chooses to emphasize and how he chooses to characterize people and events. He admires Jefferson a bit too much to blaze away with both barrels, although he doesn't pull punches where appropriate, but he's most fun when attacking other targets he really despises:

Dumas Malone, Jefferson's most revered biographer, continued in this tone as late as 1985, writing that for Madison Hemings to claim descent from his master was no better than "the pedigree printed on the numerous stud-horse bills that can be seen posted around during the Spring season. No matter how scrubby the stock or whether the horse has any known pedigree, owners invented an exalted stock for their property." In other words, for many decades historians felt themselves able to discount [James] Callender's story because it had originated with a contemptible bigot who had a political agenda. But one cannot survey the steady denial, by a phalanx of historians, of the self-evident facts without appreciating that racism, sexism, and political partisanship have also been manifested in equally gross ways, and by more apparently 'objective' means, and at the very heart of our respectable academic culture.

"The Christian King of Great Britain"

The ever-refreshing Christopher Hitchens (whose brief biograph of Jefferson I enjoyed, although I wish it had been more acerbic) has an interesting article up at City Journal: "Jefferson Versus the Muslim Pirates". Here's a snippet:

The ever-refreshing Christopher Hitchens (whose brief biograph of Jefferson I enjoyed, although I wish it had been more acerbic) has an interesting article up at City Journal: "Jefferson Versus the Muslim Pirates". Here's a snippet:How many know that perhaps 1.5 million Europeans and Americans were enslaved in Islamic North Africa between 1530 and 1780? . . .

Some of this activity was hostage trading and ransom farming rather than the more labor-intensive horror of the Atlantic trade and the Middle Passage, but it exerted a huge effect on the imagination of the time—and probably on no one more than on Thomas Jefferson. Peering at the paragraph denouncing the American slave trade in his original draft of the Declaration of Independence, later excised, I noticed for the first time that it sarcastically condemned “the Christian King of Great Britain” for engaging in “this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers.” The allusion to Barbary practice seemed inescapable.

Lemmon v. People XIV: Did the Free States Have an Obligation to Respect the Institution of Slavery?

The dissenting opinion in the New York Court of Appeals (discussed in several of the earlier posts) provides one possible approach, but I have been struggling to convince myself that the Taney court would have embraced so nationalistic and anti-state's rights an approach. It is certainly true that Taney demonstrated that he was prepared to write extremely nationalistic opinions if that is what it took to defend slavery: see my post on Prigg v. Pennsylvania (again, just use the tag). It is also certainly true that Taney's defense of slavery was so frenzied that it led to intellectual dishonesty and incoherence (see Dred Scott). Even so, the approach taken by the dissenter in Lemmon is based on such a "loose" construction that I keep thinking that it would have given even Roger Taney pause.

The good news is that there may be light at the end of the tunnel. Paul Finkelman's book, An Imperfect Union: Slavery, Federalism, and Comity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 1981), reportedly refers to unpublished notes and drafts in Taney's papers that indicate that he was preparing to write a decision holding that "the free states of the Union" had "an obligation . . . to respect the institution of slavery," even within their own borders. I've ordered a copy of Finkelman's book. Hopefully, it will provide some clue as to the reasoning that Taney contemplated using to justify such a holding. If so, I will report and then analyze the reasoning.

References to Finkelman's book and the existence of Taney's notes appear in James McPherson's Battle Cry of Freedom (at 180) and in Chandra Manning's recently-published What This Cruel War Was Over (at 17 and fn.33 at 230). I had hoped to find discussion of Taney's notes, and perhaps the notes themselves, on the web, but I struck out. If anyone has found them on the web or otherwise in publicly-available form, I'd be delighted to hear from you.

The District of Columbia Emancipation Act

I'm a few days late, but 145 years ago last week (April 16, 1862) President Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, ending slavery in the District. The Act provided for the immediate emancipation of the District's slaves and compensation to loyal Unionist masters. Compensation was limited to no more than $300 for each slave and $1MM in total.

I'm a few days late, but 145 years ago last week (April 16, 1862) President Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, ending slavery in the District. The Act provided for the immediate emancipation of the District's slaves and compensation to loyal Unionist masters. Compensation was limited to no more than $300 for each slave and $1MM in total.The Act established a Commission, composed of three members appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Former masters were required within 90 days to submit claims to the Commission. Within nine months, the Commission was to report its findings and "appraisement" to the Secretary of the Treasury, who was then to authorize payment. The federal government ultimately paid almost $1MM in compensation for the freedom of 3,100 slaves.

Since you can read about the Act in a number of places, I thought I'd focus on one particular issue: was the Act constitutional? The question, as it turns out, is quite interesting.

The Fifth Amendment provides (emphasis added):

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

One issue that immediately stands out is whether the limitation on compensation of up to $300 per slave was "just." Immediately before the War, the market value of prime field hands was more than $1,000. I don't know what the market value of slaves in the District was on April 15, 1862. However, if it exceeded $300, the law awarded patently inadequate compensation and was unconstitutional in that respect.

But there was an even more serious objection. The Fifth Amendment required that any taking, even a properly-compensated one, be "for public use." Emancipation was certainly effected for a public purpose, but the emancipated slaves were not being taken for public use. The Act did not provide that the government was going to take title to the freedmen or put them to work involuntarily. To the contrary, the whole idea was that the former slaves were free.

Interestingly, the public use/public purpose distinction remains a "hot button" topic in constitutional law today, epitomized by the Supreme Court's decision in Kelo v. City of New London (2005). There are thousands of web pages devoted to Kelo, so I won't go into great detail, but briefly the City condemned and took private real property (people's homes) pursuant to a development plan designed to revitalize an allegedly distressed area, resulting in increased jobs and tax income. The City was not going to retain title to the property, but rather turn the land over to developers.

The Supreme Court upheld the taking as constitutional 5-4. In his majority opinion, Justice Stevens expressly conceded that the taking was not for "public use." Nonetheless, the fact that it was for a "public purpose" make the taking constitutional.

Kelo, however, was the culmination of a line of Supreme Court cases developed in the mid-Twentieth Century. Although Justice Stevens tried to trace concept back further (he cited a Nevada state court case from 1876), even he conceded that, "in the mid-19th century" "use by the public" was generally considered "the proper definition of public use."

In short, measured by constitutional understanding at the time, the District of Columbia Emancipation Act was probably unconstitutional both because it did not provide for "just compensation" and because the takings it effected were not for "public use."

Saturday, April 21, 2007

The Know Nothings Are Alive and Well

All those stupid history books claim that the American (aka Know Nothing) party died c. 1857. It turns out they're all wrong. Michael Novak at NRO points out that the KNs are doing just fine.

All those stupid history books claim that the American (aka Know Nothing) party died c. 1857. It turns out they're all wrong. Michael Novak at NRO points out that the KNs are doing just fine.Was Slavery on the Way Out in 1860? III

Worldwide demand for cotton grew dramatically during the antebellum period, and particularly during the 1850s, increasing the price of slaves. Gavin Wright argues that, independent of the War, demand for cotton leveled off beginning in the 1860s. Had southern production not fallen dramatically during and after the War (production did not return to 1859 levels until about 1880), this would have led to lower cotton prices -- and a dramatic fall in the price of slaves as well.

Several conclusions follow, he argues. First, as noted in my immediately preceding post, he contends that the high price of slaves intensified slaveholder radicalism in defense of slavery. He therefore wonders whether, if secession and war had been avoided in 1860-61, the intensity of southern feelings might have ebbed as slave prices dropped, increasing the chances that war might have been avoided altogether.

Second, if there had been no war, and if slavery had survived into the 1870s and 1880s, the south nonetheless would have faced significant economic changes as southerners struggled to reallocate slave labor to other uses -- and potentially significant social disruption when white workers protested increasing competition with slaves.

Nonetheless, Professor Wright's best guess is that, without the war, slavery would have survived. War might have been unnecessary, but at a terrible cost:

Several conclusions follow, he argues. First, as noted in my immediately preceding post, he contends that the high price of slaves intensified slaveholder radicalism in defense of slavery. He therefore wonders whether, if secession and war had been avoided in 1860-61, the intensity of southern feelings might have ebbed as slave prices dropped, increasing the chances that war might have been avoided altogether.

Second, if there had been no war, and if slavery had survived into the 1870s and 1880s, the south nonetheless would have faced significant economic changes as southerners struggled to reallocate slave labor to other uses -- and potentially significant social disruption when white workers protested increasing competition with slaves.

Nonetheless, Professor Wright's best guess is that, without the war, slavery would have survived. War might have been unnecessary, but at a terrible cost:

As slave prices fell and receded in prominence, Southern vulnerability to rhetorical attacks might have diminished as well. If this analysis is correct, then the missed opportunities for delay and compromise during 1859-61 loom larger and larger historically. But as difficult as the proposition is for twentieth-century Americans to accept, it was slavery as well as the Union that would have been preserved for a long time. Slavery would have faced internal political and economic pressures in the South, but the notion that slavery would have faded away peacefully in the late nineteenth century has always been a wishful chapter in historical fiction, not part of a plausible counterfactual history.

Another Slaveowner-Homeowner Analogy

Last year, Kevin Levin mentioned an analogy between home ownership and slave ownership as a possibly useful way to explain the way that slavery shaped antebellum southern society. I thought immediately of that post yesterday when I ran across the same analogy, although used for a quite different purpose.

The analogy appears in Gavin Wright's The Political Economy of the Cotton South: Households, Markets, and Wealth in the Nineteenth Century (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 1978). I probably understood about half of it, but even so it was apparent to me why it is regarded as the authoritative volume on antebellum southern political economics. Short (184 pages of text, including footnotes [real footnotes!]), the book is incredibly well written.

The book's argumentation is a model of the sort I like. In a recent post, I complained that historians were too often like ships passing in the night. There are no such ships here. When discussing a topic, Professor Wright regularly lays out the arguments that others have made, together with the facts and evidence that tends to support each. He then carefully weighs and analyzes the facts and arguments, pointing out factual gaps, contrary evidence and logical fallacies, until he arrives at his own conclusion, which may favor a particular view or be a synthesis of competing or apparently contradictory positions. The clarity of the writing and methodology makes it easy for the reader to evaluate the conclusions (unless, of course, you're an economics idiot like me!).

I also like the fact that Professor Wright does not overstate his case. Sometimes, his conclusions are firm. But where he does not believe the evidence admits a definitive answer, he does not hesitate to admit that the answer he proposes is simply the one that best reconciles the known facts.

At all events, Professor Wright raises the analogy between slave ownership and home ownership "to explain why Southerners went to extremes in insisting on absolute guarantees of their rights by the federal government everywhere in the Union."

Slave property was extremely valuable in the 1850s, with the price of slaves far in excess of cost-determined levels. High prices reflected the fact that slavery was profitable, but more importantly the higher prices embodied that profitability. The rising prices represented capital gains supported by a region-wide market (unlike land, the price of which was determined by local conditions and markets, slave prices were consistently uniform throughout the south). Those capital gains and regional market provided a unifying economic interest among slaveholders across the south. Professor Wright comments that "[i]t is difficult to think of historical cases that are remotely comparable."

Professor Wright then turns to the question quoted above. If slaveholders had so much economic value to preserve, why did they act so rashly during the 1850s? "With so much to conserve, why weren't they more conservative?"

The beginning of the answer lies in the fact that "the value of slave property was so thoroughly dependent on expectations and confidence." Moreover, that expectation and confidence was one that was region-wide. Thus each slaveowner or prospective buyer had to take into account the confidence of others throughout the market. It's best to let Professor Wright speak for himself, using the fugitive slave laws as an example:

So where, you ask, is the homeowner analogy? Well, here it comes. Again, I'll simply let Professor Wright make his own case:

I would add only that the large geographic extent of the market increased the likelihood of mistaken understanding of the concerns of others located far away. As a homeowner, I presumably have a reasonably good feel for the concerns of others in my neighborhood. But a slaveholder in, say, Georgia would have little way to know the concerns of slaveowners in, say, Kentucky. It strikes me that, with little hard information to go on, the Georgia slaveowner would likely fear the worst and thus tend to expect that Kentucky slaveholders were gravely concerned about fugitive slaves, even if they weren't.

As usual, Professor Wright does not overstate his case. He does not contend that slaveowners were basing political decisions on slave prices. He does not deny that there were many other factors at work:

The analogy appears in Gavin Wright's The Political Economy of the Cotton South: Households, Markets, and Wealth in the Nineteenth Century (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 1978). I probably understood about half of it, but even so it was apparent to me why it is regarded as the authoritative volume on antebellum southern political economics. Short (184 pages of text, including footnotes [real footnotes!]), the book is incredibly well written.

The book's argumentation is a model of the sort I like. In a recent post, I complained that historians were too often like ships passing in the night. There are no such ships here. When discussing a topic, Professor Wright regularly lays out the arguments that others have made, together with the facts and evidence that tends to support each. He then carefully weighs and analyzes the facts and arguments, pointing out factual gaps, contrary evidence and logical fallacies, until he arrives at his own conclusion, which may favor a particular view or be a synthesis of competing or apparently contradictory positions. The clarity of the writing and methodology makes it easy for the reader to evaluate the conclusions (unless, of course, you're an economics idiot like me!).

I also like the fact that Professor Wright does not overstate his case. Sometimes, his conclusions are firm. But where he does not believe the evidence admits a definitive answer, he does not hesitate to admit that the answer he proposes is simply the one that best reconciles the known facts.

At all events, Professor Wright raises the analogy between slave ownership and home ownership "to explain why Southerners went to extremes in insisting on absolute guarantees of their rights by the federal government everywhere in the Union."

Slave property was extremely valuable in the 1850s, with the price of slaves far in excess of cost-determined levels. High prices reflected the fact that slavery was profitable, but more importantly the higher prices embodied that profitability. The rising prices represented capital gains supported by a region-wide market (unlike land, the price of which was determined by local conditions and markets, slave prices were consistently uniform throughout the south). Those capital gains and regional market provided a unifying economic interest among slaveholders across the south. Professor Wright comments that "[i]t is difficult to think of historical cases that are remotely comparable."

Professor Wright then turns to the question quoted above. If slaveholders had so much economic value to preserve, why did they act so rashly during the 1850s? "With so much to conserve, why weren't they more conservative?"

The beginning of the answer lies in the fact that "the value of slave property was so thoroughly dependent on expectations and confidence." Moreover, that expectation and confidence was one that was region-wide. Thus each slaveowner or prospective buyer had to take into account the confidence of others throughout the market. It's best to let Professor Wright speak for himself, using the fugitive slave laws as an example:

Such a financial asset involves external effects of region-wide scope: even if I attach no importance whatsoever to fugitive slave legislation as it effects [sic] my own slaves, if I think that you (any nontrivial number of slaveowners or buyers) attach some importance to it, then the issue affects me financially and I have good reason to become a political advocate of strong guarantees.

So where, you ask, is the homeowner analogy? Well, here it comes. Again, I'll simply let Professor Wright make his own case:

The closest analogy today is the behavior of homeowners. A house is typically the largest asset owned by a family -- indeed families are usually heavily in debt if they buy a house -- and here also the value of the property depends on the opinions and prejudices of others. In this case as well, prejudice and intolerance are intensified by market forces. I may not really care whether a black family moves next door, but, if I feel that others care, I will be under financial pressure to share their views or at least act as though I do. The main difference between the housing case and slavery are that many owners held more than one slave, and that for slavery these were not "neighborhood effects" limited to a small geographic area but system-wide externalities, so that a threat to slavery anywhere was a threat to slaveowners everywhere. The effect was to greatly exacerbate the response to any threat.

I would add only that the large geographic extent of the market increased the likelihood of mistaken understanding of the concerns of others located far away. As a homeowner, I presumably have a reasonably good feel for the concerns of others in my neighborhood. But a slaveholder in, say, Georgia would have little way to know the concerns of slaveowners in, say, Kentucky. It strikes me that, with little hard information to go on, the Georgia slaveowner would likely fear the worst and thus tend to expect that Kentucky slaveholders were gravely concerned about fugitive slaves, even if they weren't.

As usual, Professor Wright does not overstate his case. He does not contend that slaveowners were basing political decisions on slave prices. He does not deny that there were many other factors at work:

The strength of the argument is that it is not based on an exclusively economic nor exclusively rational conception of motivation and behavior. Fear, racism, misperceptions, and long-run strategic calculations all undoubtedly did exist. The point is that economic forces served to intensify every other motive for the South's insistence on guarantees of the rights of slaveholders and even the quest for a virtual endorsement of slavery by the North. The argument does not imply that Southern politicians were scrutinizing slave prices in their every action; but the widespread concern over property values created a situation in which an ambitious politician could easily mobilize a constituency by strongly insisting on absolute guarantees for slaveowners' rights.

Wednesday, April 18, 2007

William Freehling on the Michael Holt Issue

There is no doubt in my mind that Michael Holt's The Political Crisis of the 1850s is one of the most important books written about the causes of the Civil War in the past thirty years. In it, Professor Holt posits that any theory about why the south seceded must explain why the seven lower southern States seceded based merely on President Lincoln's election, while the remaining slaveowning States did not do so.

There is no doubt in my mind that Michael Holt's The Political Crisis of the 1850s is one of the most important books written about the causes of the Civil War in the past thirty years. In it, Professor Holt posits that any theory about why the south seceded must explain why the seven lower southern States seceded based merely on President Lincoln's election, while the remaining slaveowning States did not do so.Professor Holt argues that the traditional explanation -- that the middle and border southern states had fewer slaves, measured as a percentage of population or as a percentage of white slaveowning families -- is insufficient. (See, for example, the chart at page 229 of the Norton paperback edition and surrounding discussion.) He argues that the crucial determinant is the historical strength of two-party competition in each State. His analysis of interparty competition purports to show that, in the period immediately before the War, interparty competition substantially decreased in the "lower south" (the seven States that seceded before Lincoln's inauguration) but remained steady in the other slaveholding States.

In an earlier post, I mentioned that, as I read William Freehling's The Road to Disunion II, I would be on the lookout for any discussion of this issue. Although I am not quite finished with the book, it is apparent that Professor Freehling's primary interest lies with why and how the lower southern States seceded. That in itself is a fascinating story, and Professor Freehling sheds light on that story that I, at least, have never encountered, and that makes his book invaluable.

However, for better or worse, it appears that the eventual secession of four other slaveholding States is of less interest to him. (In addition, or in the alternative, a footnote suggests that that Professor Freehling was discouraged from re-ploughing the same ground so admirably trodden by Daniel Crofts.) As a result, he has little to say on Professor Holt's issue, and when he does discuss it he seems to sit squarely on the fence, suggesting that both differences in slave populations and differences in party competitiveness explain the different reactions to President Lincoln's election:

A solid South [in favor of secession] would have to transcend the social fact that 47 percent of the Lower South's peoples were slaves compared to 32 percent of the Middle South's and 13 percent of the Border South's, the political fact that that ex-Whigs (later Americans or Know-Nothings and yet later Oppositionists and still later Constitutional Unionists) had remained very competitive in the Upper South while becoming largely unelectable in the Lower South, and the later electoral fact that John Breckenridge had received 56 percent of the Lower South's 1860 popular presidential vote compared to 32 percent in the Border South.

Professor Freehling may well be right, but this stray sentence simply does not prove it. In particular, the statistics, while presumably perfectly accurate, evade the statistics that Professor Holt cites. If slaves and slaveholding are sufficient causes, why did Texas (28% white families owning slaves) secede, while Virginia (27.3%), North Carolina (29%), Tennessee (24.9%), and even Kentucky (23.5%) did not? Professor Freehling's impressionistic statement simply does not burrow sufficiently deep to grapple with the issues that Professor raises.

I am not, by the way, a member of the school that contends that slavery had nothing to do with secession. To the contrary, I think it had everything to do with it. But at the same time I think that Professor Holt has presented arguments that strongly suggest that the interaction is, somehow, far more complex than most consider it to be. My disappointment arises precisely from the fact that I was hoping that a historian of Professor Freehling's stature would give this issue his close attention.

Tuesday, April 17, 2007

More Thoughts on William Freehling: A Coda to the Footnotes

I feel somewhat guilty having criticized Professor Freehling in earlier posts. To make amends, I should emphasize that a review of the footnotes (I know, they're really endnotes) reveals an encyclopedic knowledge of both primary and secondary sources. Nor do titles appear solely for the sake of citing them. For example, several footnotes discuss and sometimes intelligently criticize books such as J. Mills Thornton's Politics and Power in a Slave Society, Lacy Ford's Origins of Southern Radicalism (both discussed here), William Barney's The Secessionist Impulse, and Charles Dew's Apostles of Disunion.

A surprising number of footnotes (in addition to the one I discussed earlier) use the word "guess" or otherwise acknowledge that historical interpretation is an uncertain task.

Perhaps, then, it's best to say that, in order to appreciate The Road to Disunion II and how carefully Professor Freehling has considered the alternatives before reaching his conclusions, the footnotes are required reading.

A surprising number of footnotes (in addition to the one I discussed earlier) use the word "guess" or otherwise acknowledge that historical interpretation is an uncertain task.

Perhaps, then, it's best to say that, in order to appreciate The Road to Disunion II and how carefully Professor Freehling has considered the alternatives before reaching his conclusions, the footnotes are required reading.

Sunday, April 15, 2007

More Thoughts on William Freehling: A Footnote

In The Road to Disunion II, William W. Freehling has a footnote (actually an endnote) discussing Professor McCurry's book that exemplifies the kind of writing that I admire in historians. It sets forth an issue as to which they disagree and explains why. It also explicitly acknowledges that his conclusion is an inference, not a certainty. In short, it uses precisely the sort of approach that I wish Professor Freehling had employed throughout the book.

The endnote appears at the end of a paragraph of text in which Professor Freehling is discussing why non-slaveowning white yeomen in the South Carolina lowcountry supported planters. Professor Freehling's typically frustrating prose (at 360-61) conveys more impression than fact:

Lowly whites as black belt political superiors had no qualms about elevating squires to the legislature or about ousting abolitionists from the neighborhood. In the paramilitary societies that patrolled the lowcounty in the fall of 1860, nonslaveholders paraded beside their richer neighbors, proudly keeping blacks ground under. The patriarchal obligation of all white men to guard their wives, gratifying to poor men's chauvinistic egos, included the necessity to keep a 90 percent black majority from murdering white dependents.

It is precisely this sort of passage that makes one feel queasy, because it presents what are presumably inferences without qualification or acknowledgment of uncertainty. It does not even acknowledge that they are inferences.

Then, in the endnote (at 569), Professor Freehling says precisely what you wish he had said in the text:

This may be a better (or worse) guess than Stephanie McCurry's speculation that white yeomen massed behind wealthier men's domination over dependent blacks in order to preserve white males' domination over dependent wives. We are all guessing from missing evidence about yeomen's motives; that is usually a difficulty with history from the bottom up. But I've seen no hint that South Carolina white males feared, or had the slightest reason to fear, female domination before the war. In contrast, I've seen much evidence that fear of racial unrest afflicted lowcountry whites -- and plenty of reason for that fear. Still, Professor McCurry's gender-based speculation is intriguing; her evidence of poorer whites' full participation in 1860 paramilitary pressures is irrefutable; and I applaud her success in making the hitherto invisible lowcountry white nonslaveholders highly visible in the secession story. . ..

You may or may not think that Professor Freehling characterizes Professor McCurry's thesis with absolute precision; you may or may not agree that Professor Freehling's "guess" is the better one; but at least you know what conclusion he draws, why he draws it, and why he believes that it's a better inference than Professor McCurry's. Even more significantly, he acknowledges with utter candor the uncertainty that characterizes so much of the historical art.

Saturday, April 14, 2007

Some Thoughts on William Freehling

Occasionally, this sort of "you are there" writing can be fun. Take, for example, his chapter on the Democratic convention held in Charleston, South Carolina in April 1860. I rather enjoyed the descriptions of the difficulties that travelers encountered just getting to Charleston and the discomforts that the conventioneers experienced after they arrived, from pickpockets to unexpectedly steamy weather that left attendants sleepless at night and sweat drenched during the day in the airless convention hall. Similarly, and on a somewhat different level, he does a good job giving you a real feel for the claustrophobic salons of Charleston that gave rise to hothouse dreams of secession.

But the negatives far outweigh the positives. First, Professor Freehling is, I regret to say, a leaden wordsmith. As a result, most of his attempts to create dramatic tension simply fall flat because the reader is too busy shaking his head in stunned disbelief at the overblown oratory and inappropriate word selection.

More seriously, I fear that Professor Freehling's tendency to present dramatic characters and incidents to illustrate points creates the suspicion, justified or not, that the casting and plotmaking is just a bit too neat. Compounding the problem, the "up close and personal" technique often makes it difficult for the reader to evaluate the lessons the author draws from and the arguments he makes based upon the dramatic incidents he recreates.

Together, these problems mean that, for me at least, the writing technique is not merely distracting; it is also substantively counterproductive, because the reader feels less confident about the conclusions drawn than he otherwise would.

This is no doubt unfair to Professor Freehling, who has lived and breathed the antebellum period and these issues most of his life. Some of his footnotes, which I hope to discuss in future posts, make clear that he has thought long and hard about the issues and considered competing views before reaching his conclusions. But I for one would have preferred more distance and a more overtly "academic" tone. I also would have liked more explicit discussion as to why he has rejected other interpretations of various events and issues.

Come to think of it, I guess this last complaint is a pet peeve I have about much historical writing. Too often, historians discussing an issue seem to pass each other in the night. I would prefer to see more acknowledgment and discussion of other views and why the author disagrees with them: "Professor A says the answer is X; Professor B says it's Y; I think they're both wrong and that the answer is Z. Here is why they disagree with each other, and here is how and why I come to the conclusion I do."

Tuesday, April 10, 2007

Imus

Over at Civil War Memory, Kevin Levin is mystified as to why Don Imus felt free to use the phrase "nappy-headed hos" on his show:

Over at Civil War Memory, Kevin Levin is mystified as to why Don Imus felt free to use the phrase "nappy-headed hos" on his show:What I don't understand is why as a society we continue to tolerate this kind of language. Don Imus has one of the most popular radio talk shows (broadcasted [sic] live on MSNBC) and is a regular stop for politicians on the campaign trail, well-regarded journalists, and other popular figures. What I have difficulty understanding is the fact that he apparently felt comfortable enough to say those things at all. There was no hesitation in sharing these thoughts over the wires owned by NBC.

Kevin has apparently (a) never listened to Imus, (b) never ridden the New York City subway, (c) never listened to rap music, and (d) never seen a Spike Lee movie. It is perfectly obvious that Imus, affecting, as he often does, to be a super-cool urban hipster, slipped over into thinking that he could talk "black."

Kevin is right to wonder "why we as a society continue to tolerate this kind of language" -- but it's strange that he hasn't noticed that "society" has been "tolerating" ("rewarding" might be a better term) "this kind of language" for many years.

UPDATE: Michelle Malkin is, as usual, spot on:

Let's stipulate: I have no love for Don Imus, Al Sharpton, or Jesse Jackson. I repeat: A pox on all their race-baiting houses.

Let's also stipulate: The Rutgers women's basketball team didn't deserve to be disrespected as "nappy-headed hos." No woman deserves that. I agree with the athletes that Imus's misogynist mockery was "deplorable, despicable and unconscionable." And as I noted on Fox News's O'Reilly Factor this week, I believe top public officials and journalists who have appeared on Imus's show should take responsibility for enabling Imus—and should disavow his longstanding invective.

But let's take a breath now and look around. Is the Sharpton & Jackson Circus truly committed to cleaning up cultural pollution that demeans women and perpetuates racial epithets? Have you seen the Billboard Hot Rap Tracks chart this week?

Sunday, April 08, 2007

Alger Hiss

An "Event Release" by NYU touting a conference entitled "Alger Hiss and History" seems to suggest that significant questions remain concerning Hiss's guilt:

An "Event Release" by NYU touting a conference entitled "Alger Hiss and History" seems to suggest that significant questions remain concerning Hiss's guilt:The 1948 Alger Hiss case was a major moment in post-World War II America that reinforced Cold War ideology and accelerated America’s late-1940’s turn to the right. When Hiss, one of the nation’s more visible New Dealers, was accused of spying for the Soviet Union and convicted of perjury, his case was seen as one of the most significant trials of the 20th century, helping to discredit the New Deal, legitimize the red scare, and set the stage for the rise of Joseph McCarthy.

As scholars have gained access to the archives in the former Soviet Union and more U.S. documents have been declassified, there has been renewed debate about the Hiss case itself and the larger issues of repression, civil liberties, and internal security that many believe speak to current public policy and discussions.

With all due respect, there is no "debate" about the Hiss case any more. As Powerline has pointed out, the literature documenting the fact that Hiss was a Soviet agent is overwhelming. Among the books that Powerline cites, Allen Weinstein's Perjury: The Hiss-Chambers Case and Sam Tanenhaus's Whittaker Chambers: A Biography are superb. Weinstein's The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America -- The Stalin Era and Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America by John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr provide valuable information about the stunning breadth of Soviet espionage in America during the 1930s and 1940s. Another book, not mentioned by Powerline, that illuminates the period is Steven T. Usdin's fascinating Engineering Communism: How Two Americans Spied for Stalin and Founded the Soviet Silicon Valley (New Haven: Yale University Press 2005).

On a personal note, a number of years ago I had the pleasure of meeting Martin Tytell, the man commissioned by Hiss's attorneys to duplicate the prosecution's Woodstock typewriter, and his wife Pearl Tytell. They were working out of a small office on Fulton Street, in lower Manhattan, every inch of which was covered with typewriters, typewriter parts, piles of paper and other miscellaneous junk. The advent of the computer had decimated Martin's business. Pearl was a questioned document examiner, and I wound up using her as an expert witness in a case that went to trial. She must have been almost eighty at the time, sharp, feisty and tough as nails behind a proper exterior. The opposing attorney never laid a glove on her. Here's to you, Pearl!

Freehling on Secession?

Michael Holt has argued that the lower south promptly seceded after Lincoln's election while the middle and upper south did not because, among other things, the lower south had never developed a viable two-party system. Cotton south Democrats thus lacked the experience of falling out of power and then rallying and coming back in the next election. When Lincoln won in 1860, they did not see it as a potentially temporary setback, to be overcome by normal democratic processes, but rather the beginning of permanent minority.

Michael Holt has argued that the lower south promptly seceded after Lincoln's election while the middle and upper south did not because, among other things, the lower south had never developed a viable two-party system. Cotton south Democrats thus lacked the experience of falling out of power and then rallying and coming back in the next election. When Lincoln won in 1860, they did not see it as a potentially temporary setback, to be overcome by normal democratic processes, but rather the beginning of permanent minority.One thing for which I've been on the lookout for, while reading The Road to Disunion II, is whether Professor Freehling agrees with Holt's theory, in whole or in part. Here's the first suggestion of a positive answer I've encountered (at 96):

Thus where the heavily enslaved Lower South's experience with nativism [the American Party in 1854-56] had yielded a largely one-party system, with the hapless ex-Whig remnant in position only to carp at the proslavery Democracy, the lightly-enslaved Border South had regenerated a competitive two-party system, with the powerful ex-Whig fragment in position to defeat the Democracy. The Lower South and Border South had generated different political institutions, compounding their different social institutions. In 1860, the borderland's powerful surviving ex-Whig partisan organizations would give the region's Unionist Party a leg up in defeating secessionists. But in the Lower South, the uncompetitive ex-Whigs would offer no such institutional bulwark against disunion.

Saturday, April 07, 2007

Cotton

Am I crazy? Doesn't every book I've ever read about the antebellum south go on and on about how destructive cotton is of the soil?

And then I read this:

The accompanying footnote cites a number of technical articles "[o]n the relatively small demands made by cotton upon the plant food of the soil in comparison with other crops."

Gavin Wright, The Political Economy of the Cotton South: Households, Markets, and Wealth in the Nineteenth Century (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 1978) at 17.

And then I read this:

[The westward expansion of the cotton belt], from inferior to superior soil, has given rise to greatly exaggerated conceptions of the extent of soil exhaustion and erosion in the Southeast. Cotton is not in fact a highly exhaustive crop, and the gutted, windswept hills of the Piedmont, so vividly described by Olmstead and De Bow, were as much the result of abandonment as its cause.

The accompanying footnote cites a number of technical articles "[o]n the relatively small demands made by cotton upon the plant food of the soil in comparison with other crops."

Gavin Wright, The Political Economy of the Cotton South: Households, Markets, and Wealth in the Nineteenth Century (New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 1978) at 17.

The Road to Disunion II: Secessionists Triumphant

I am wending my way through William Freehling's Road to Secession Volume II. After about 150 pages, my reaction is that this should not be the first book you should read on the period 1854-1861. Professor Freehling is too idiosyncratic a writer for that. Putting aside his offputting writing style, the good professor tends to zero in on particular topics that interest him -- for example, the tensions inherent in different southern justifications of slavery -- and then gives comparatively brief treatment to others.

I am wending my way through William Freehling's Road to Secession Volume II. After about 150 pages, my reaction is that this should not be the first book you should read on the period 1854-1861. Professor Freehling is too idiosyncratic a writer for that. Putting aside his offputting writing style, the good professor tends to zero in on particular topics that interest him -- for example, the tensions inherent in different southern justifications of slavery -- and then gives comparatively brief treatment to others.His discussion of Kansas and Lecompton is a good example. You can tease out of the discussion the basic underlying facts, but Professor Freehling is really more interested in focusing on particular issues. Why were southerners so hell-bent on Kansas? Why did President Buchanan wind up supporting the Lecompton Constitution? I'm pretty sure that, if I did not already have the basic facts in hand, I would be looking for a more straightforward description of events and the supporting evidence.

That said, if you've got some background, Professor Freehling offers interesting insights, and you shouldn't miss his book. Take the last issue mentioned above, for example. Elsewhere, you can discover that the evidence is strong to the point of conclusive that, before he went to Kansas, Robert Walker sought and obtained assurances from President Buchanan that Buchanan would support him in demanding that any Kansas constitution be submitted to a popular referendum. Yet after Walker took this position, based on Buchanan's promise, Buchanan reversed course, disavowed his promise, supported the Lecompton Constitution, and went a long way to destroying his presidency, his party and the country in the process. Why on Earth did Buchanan pursue so destructive a course?

Professor Freehling paints a highly plausible picture of Buchanan torn by conflicting loyalties, personal and political. Buchanan's jovial good friend and trusted political confidant Howell Cobb, Secretary of the Treasury in Buchanan's cabinet, felt strongly both that the federal government should not reject an application for statehood simply because the work of a duly elected state convention was not ratified by a popular referendum, and that it was foolish and counterproductive for the state convention to refuse to submit its work to a referendum. With Buchanan's express or tacit consent, Cobb took up the laboring oar to try to insure that the Lecompton convention endorsed a referendum. However, because he believed that the federal government could not and should not dictate to a state on such a matter, he sought to persuade rather than order the convention to provide for a referendum.

When this tactic failed, Buchanan was left with an extremely awkward choice, on both the personal and political levels. If he repudiated the Lecompton Constitution, he would in effect be repudiating his friend Cobb's work and principles, risking mass resignations from the cabinet in the process. He therefore chose the alternate course, justifying his position to himself by relying on the fact that the Lecompton convention had provided for a partial referendum, and convincing himself that any negative political ramifications would be only temporary.

Professor Freehling frankly admits that the psychological picture he paints represents his best guess based on inferences from the available evidence and is not conclusive, but that refreshing admission only makes it the more convincing.

Thursday, April 05, 2007

Three Cheers for Herodotus!

I really like Herodotus. He seems like a guy you would have wanted to have over for a dinner party. Give him a good meal, a couple of kraters of wine, and get him talking.

I really like Herodotus. He seems like a guy you would have wanted to have over for a dinner party. Give him a good meal, a couple of kraters of wine, and get him talking.When contemporary historians deny that "real" history can include good storytelling, I think of Herodotus, the storyteller extraordinaire. Now, it turns out that his careful recording of outrageous and colorful local stories may have captured a bit of truth that others missed:

Geneticists have added an edge to a 2,500-year-old debate over the origin of the Etruscans, a people whose brilliant and mysterious civilization dominated northwestern Italy for centuries until the rise of the Roman republic in 510 B.C. Several new findings support a view held by the ancient Greek historian Herodotus — but unpopular among archaeologists — that the Etruscans originally migrated to Italy from the Near East.

* * *

An even more specific link to the Near East is a short statement by Herodotus that the Etruscans emigrated from Lydia, a region on the eastern coast of ancient Turkey. After an 18-year famine in Lydia, Herodotus reports, the king dispatched half the population to look for a better life elsewhere. Under the leadership of his son Tyrrhenus, the emigrating Lydians built ships, loaded all the stores they needed, and sailed from Smyrna (now the Turkish port of Izmir) until reaching Umbria in Italy.

Despite the specificity of Herodotus’ account, archaeologists have long been skeptical of it. There are also fanciful elements in Herodotus’ story, like the Lydians’ being the inventors of games like dice because they needed distractions to take their minds off the famine. And Lydian, unlike Etruscan, is definitely an Indo-European language. Other ancient historians entered the debate. Thucydides favored a Near Eastern provenance, but Dionysius of Halicarnassus declared the Etruscans native to Italy.

* * *

With the geneticists in disarray, archaeologists had been able to dismiss their results. But a new set of genetic studies being reported seems likely to lend greater credence to Herodotus’ long-disputed account.

Three new and independent sources of genetic data all point to the conclusion that Etruscan culture was imported to Italy from somewhere in the Near East.

* * *

As for Herodotus, Ms. Jovino said she believed, liked most modern historians, “that he does not always report real historical facts.” often referring to oral tradition.

But at least on the matter of Etruscan origins, it seems that Herodotus may yet enjoy the last laugh.

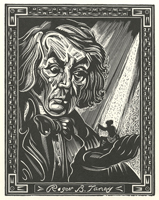

Roger B. Taney

Why does this seem to place Chief Justice Taney in such a different light? At the same time he was declaring that blacks were not, and never could be, citizens:

Why does this seem to place Chief Justice Taney in such a different light? At the same time he was declaring that blacks were not, and never could be, citizens:Roger B. Taney gradually manumitted almost all of [his] slaves. None of his liberated slaves, wrote . . . Taney at the time of his . . . Dred Scott Decision, "have disappointed my expectations . . . They were worthy of freedom; and knew how to use it."

William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion, Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant, 1854-1861 (New York: Oxford University Press 2007) at 111.

Monday, April 02, 2007

Is Zbigniew Brzezinski on Drugs?

The Herald-Sun reports that Zbigniew Brzezinski said the following the other day at Duke:

William Shawcross reportedly asks: "Outrageous, or demented?"

Brzezinski said there's no reason to think a bloodbath would necessarily follow a U.S. withdrawal.

"We expected that the U.S. leaving Vietnam would result in massive killings and genocide and so forth, and collapse of the dominoes in Southeast Asia," he said. "It didn't happen. How certain are we of the horror scenarios that have been mentioned in what will take place in Iraq?"

William Shawcross reportedly asks: "Outrageous, or demented?"

Sunday, April 01, 2007

Lemmon v. People XIII: What If . . .

Earlier this year, I published a number of posts concerning the New York Court of Appeals decision in Lemmon v. People (1860), in which the court held that even the transitory presence of a slave in the State of New York made the slave free. (You can find those posts by clicking on the "Lemmon v. People" link at the right.) At the time, Republicans expressed concern that the Supreme Court of the United States might use the case, or another like it, as a vehicle to extend the Dred Scott decision by holding that free states could not constitutionally bar or free slaves brought into those states by their masters.

Earlier this year, I published a number of posts concerning the New York Court of Appeals decision in Lemmon v. People (1860), in which the court held that even the transitory presence of a slave in the State of New York made the slave free. (You can find those posts by clicking on the "Lemmon v. People" link at the right.) At the time, Republicans expressed concern that the Supreme Court of the United States might use the case, or another like it, as a vehicle to extend the Dred Scott decision by holding that free states could not constitutionally bar or free slaves brought into those states by their masters.The argument in Lemmon was held before the New York Court of Appeals on January 24, 1860. The next day, the New York Times reported on the arguments, in detail. Those arguments included the slaveowner's (really Virginia's) arguments that New York laws purporting to make free slaves who entered the state even on a transitory basis violated the United States Constitution.

Abraham Lincoln delivered his Cooper Union speech just one month later, on February 27, 1860. Although he did not specifically mention Lemmon, he may be have been referring to the case in the following passage describing the threatened "overthrow of our Free-State Constitutions:"

The question recurs, what will satisfy them [the southern people]? Simply this: We must not only let them alone, but we must somehow, convince them that we do let them alone. This, we know by experience, is no easy task. We have been so trying to convince them from the very beginning of our organization, but with no success. In all our platforms and speeches we have constantly protested our purpose to let them alone; but this has had no tendency to convince them. Alike unavailing to convince them, is the fact that they have never detected a man of us in any attempt to disturb them.

These natural, and apparently adequate means all failing, what will convince them? This, and this only: cease to call slavery wrong, and join them in calling it right. And this must be done thoroughly - done in acts as well as in words. Silence will not be tolerated - we must place ourselves avowedly with them. Senator Douglas' new sedition law must be enacted and enforced, suppressing all declarations that slavery is wrong, whether made in politics, in presses, in pulpits, or in private. We must arrest and return their fugitive slaves with greedy pleasure. We must pull down our Free State constitutions. The whole atmosphere must be disinfected from all taint of opposition to slavery, before they will cease to believe that all their troubles proceed from us.

I am quite aware they do not state their case precisely in this way. Most of them would probably say to us, "Let us alone, do nothing to us, and say what you please about slavery." But we do let them alone - have never disturbed them - so that, after all, it is what we say, which dissatisfies them. They will continue to accuse us of doing, until we cease saying.

I am also aware they have not, as yet, in terms, demanded the overthrow of our Free-State Constitutions. Yet those Constitutions declare the wrong of slavery, with more solemn emphasis, than do all other sayings against it; and when all these other sayings shall have been silenced, the overthrow of these Constitutions will be demanded, and nothing be left to resist the demand. It is nothing to the contrary, that they do not demand the whole of this just now. Demanding what they do, and for the reason they do, they can voluntarily stop nowhere short of this consummation. Holding, as they do, that slavery is morally right, and socially elevating, they cannot cease to demand a full national recognition of it, as a legal right, and a social blessing.

(Emphasis added)

As it turned out, the United States Supreme Court did not have an opportunity to consider whether to reverse Lemmon. Even so, it's interesting to consider whether it would have, or at least might have, done so.

The biggest problem in making such a hypothetical prediction lies in the Supreme Court itself. Chief Justice Taney's decision in Dred Scott was profoundly dishonest from an intellectual standpoint. Taney showed himself prepared to distort history and advance ludicrous arguments in order to reach a desired result.

It's therefore necessary, I think, to conduct two inquiries, rather than one. First, what would an intellectually honest Supreme Court have done with Lemmon? Second, assuming an intense desire to reach a particular result, could the Supreme Court have stretched to reach that result and, if so, how might it have done so?

In order to avoid too long a post, I will simply set the stage. In order to reverse Lemmon, the Supreme Court would have had to clear several huge hurdles. The largest was that the states retained all sovereign powers except to the extent that they had ceded particular powers to the federal government.

It was going to be particularly difficult to argue that states had ceded their powers over the status of slavery within their borders. In Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), Justice Story had emphasized that regulation of the status of slavery was clearly a state function. It was precisely for this reason, he argued, that the Constitution included the Fugitive Slave Clause. But for the existence of that clause, a free state could declare runaway slaves free, leaving their owners and the slave states without remedy:

By the general law of nations, no nation is bound to recognise the state of slavery, as to foreign slaves found within its territorial dominions, when it is in opposition to its own policy and institutions, in favor of the subjects of other nations where slavery is recognised. If it does it, it is as a matter of comity, and not as a matter of international right. The state of slavery is deemed to be a mere municipal regulation, founded upon and limited to the range of the territorial laws. This was fully recognised in Somerset's Case, . . . decided before the American revolution. It is manifest, from this consideration, that if the constitution had not contained this clause [the Fugitive Slave Clause], every non-slave-holding state in the Union would have been at liberty to have declared free all runaway slaves coming within its limits, and to have given them entire immunity and protection against the claims of their masters; a course which would have created the most bitter animosities, and engendered perpetual strife between the different states. The clause was, therefore, of the last importance to the safety and security of the southern states, and could not have been surrendered by them, without endangering their whole property in slaves. The clause was accordingly adopted into the constitution, by the unanimous consent of the framers of it; a proof at once of its intrinsic and practical necessity.