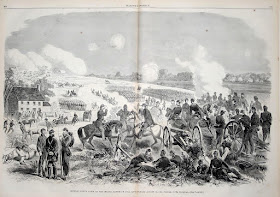

When I think of Gideon Johnson Pillow, the first image that comes to mind is that of the inept and cowardly bungler who wasted an opportunity to extricate his troops from Fort Donelson in February 1862, then fled in the middle of the night, abandoning them to their fate. Somewhat earlier, during the Mexican War, he had played an unsavory role in an attempt to discredit General Winfield Scott (referenced in the illustration below). It is interesting, therefore, to run across an event that shows Pillow in a more flattering light.

That episode was the Democratic presidential nominating convention of 1844. By way of brief background, Whig William Henry Harrison had defeated Democrat Martin Van Buren of New York in the 1840 election. Nonetheless, Van Buren remained the favorite to recapture the Democratic nomination in 1844. Despite misgivings among some southerners about Van Buren's commitment to slavery, and general nervousness about Van Buren's association with the Panic of 1837, the former president went into the convention with a majority of delegates committed to him.

Then, shortly before the convention, Van Buren made what proved to be a dramatic misstep. On April 27, 1844, the chief Democratic organ, Francis Preston Blair's Washington Globe published Van Buren's letter setting forth his position on the Texas annexation issue that exploded on the country when outgoing president John Tyler sent a proposed treaty to the Senate for ratification on April 22. In lawyerly and obscure prose full of caveats and hedges, Van Buren came out against annexation. In doing so he defied the wishes of his political ally and mentor Andrew Jackson and a groundswell of support for annexation among southern Democrats in particular.

James Knox Polk had been a firm supporter of Van Buren's renomination. Even after Van Buren's letter on annexation was published, Van Buren remained committed to the Little Magician, if only because Polk disliked Van Buren's principal competition, Lewis Cass of Michigan. In the run-up to the election, Polk positioned himself as a possible vice presidential running mate for Van Buren. However, it also belatedly occurred to Polk and his advisors – including former president Andrew Jackson – that Polk might somehow emerge as a contender for the presidential nomination if the convention deadlocked.

The Democratic convention was scheduled to open in Baltimore on Monday May 27, 1844. Polk would remain at his Tennessee plantation while the convention took place. Given the slowness of communications, Polk would be unable to influence events himself at the convention – he could not even know what was occurring on the first day until after the convention had adjourned. As a result, it was imperative that he have a skilled political operative present to manage his twin campaigns.

Enter Gideon J. Pillow. Pillow, then 37 years of age, was “one of Tennessee's most brilliant legal practitioners” who had earned Polk's lifelong gratitude and trust by saving Polk's brother from a long prison term in what seemed to be an open-and-shut case. He had enhanced his social and political prestige by becoming adjutant general in the Tennessee militia. Polk designated Pillow as his point person at the convention. As Polk explained to one of his lieutenants, Cave Johnson, before the convention:

In his book, A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, The Mexican War and the Conquest of the American Continent (from which this account is derived), Robert W. Merry describes Pillow's assignment as follows:

The task that Pillow was assigned to carry out was not an easy one. On the one hand, he had to position Polk and the Tennessee delegation as loyal to Van Buren, but without alienating other factions, to maximize Polk's chances for the vice-presidential nomination. On the other hand, he had to develop and implement a strategy to bring Polk forward as a possible compromise candidate for the presidency itself – something that had never been done before at that point – again, without raising the ire of other party leaders and their factions.

In fact, Pillow accomplished these goals with great skill. As the convention moved toward deadlock between Van Buren and Cass, Pillow kept the fractious Tennessee delegates solidly in line behind Van Buren At the same time, Pillow carefully buttonholed key leaders to suggest Polk as the solution. Working primarily through Massachusetts delegate George Bancroft and New Hampshire delegates Henry Carroll (editor of the Concord New Hampshire Patriot and State Gazette) and governor Henry Hubbard, Pillow suggested that any movement toward Polk had to be initiated by northern delegates. If a Polk boomlet appeared in the north, then, Pillow indicated, he would see to it that southern delegations joined it.

Pillow put his plan into motion after the seventh ballot. On the eighth ballot, New Hampshire announced its six votes for Polk, and shortly thereafter Massachusetts added seven more. Tennessee declared that it had not come to the convention to press the nomination of its favorite son, but now that it appeared that he had the enthusiastic support of other states it would cast its votes for him as well. By the end of the roll call, Polk had forty-four votes.

And that was enough. The next ballot, the ninth, was also the last. Virginia, which had loyally adhered to Van Buren through eight ballots, announced that it was switching its votes to Polk. Van Buren's lieutenant, Benjamin Franklin Butler of New York (no, not that Benjamin Franklin Butler), then withdrew Van Buren's name from nomination and announced that he would vote for Polk, who fully met, he said, “the Jeffersonian standard of qualification.”

About the illustration:

Then, shortly before the convention, Van Buren made what proved to be a dramatic misstep. On April 27, 1844, the chief Democratic organ, Francis Preston Blair's Washington Globe published Van Buren's letter setting forth his position on the Texas annexation issue that exploded on the country when outgoing president John Tyler sent a proposed treaty to the Senate for ratification on April 22. In lawyerly and obscure prose full of caveats and hedges, Van Buren came out against annexation. In doing so he defied the wishes of his political ally and mentor Andrew Jackson and a groundswell of support for annexation among southern Democrats in particular.

James Knox Polk had been a firm supporter of Van Buren's renomination. Even after Van Buren's letter on annexation was published, Van Buren remained committed to the Little Magician, if only because Polk disliked Van Buren's principal competition, Lewis Cass of Michigan. In the run-up to the election, Polk positioned himself as a possible vice presidential running mate for Van Buren. However, it also belatedly occurred to Polk and his advisors – including former president Andrew Jackson – that Polk might somehow emerge as a contender for the presidential nomination if the convention deadlocked.

The Democratic convention was scheduled to open in Baltimore on Monday May 27, 1844. Polk would remain at his Tennessee plantation while the convention took place. Given the slowness of communications, Polk would be unable to influence events himself at the convention – he could not even know what was occurring on the first day until after the convention had adjourned. As a result, it was imperative that he have a skilled political operative present to manage his twin campaigns.

Enter Gideon J. Pillow. Pillow, then 37 years of age, was “one of Tennessee's most brilliant legal practitioners” who had earned Polk's lifelong gratitude and trust by saving Polk's brother from a long prison term in what seemed to be an open-and-shut case. He had enhanced his social and political prestige by becoming adjutant general in the Tennessee militia. Polk designated Pillow as his point person at the convention. As Polk explained to one of his lieutenants, Cave Johnson, before the convention:

“You will find Pillow . . . a most efficient and energetic man.” . . . “Whatever is desired to be done, communicate to Genl. Pillow. He is one of the shrewdest men you ever knew, and can execute whatever is resolved on with as much success as any man who will be at Baltimore. . . . He is perfectly reliable, is a warm friend of V.B.'s [Martin Van Buren], and is my friend, and you can do so with entire safety."

In his book, A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, The Mexican War and the Conquest of the American Continent (from which this account is derived), Robert W. Merry describes Pillow's assignment as follows:

Gideon Pillow would be Polk's pivot man in Baltimore, the Tennessee delegate who would assess the scene, size up the players, identify the opportunities, and execute the plans that emerged from the chaos. . . [Other Polk associates] would be on the scene as well, gathering intelligence and helping in the effort. But Pillow would be the field commander.

The task that Pillow was assigned to carry out was not an easy one. On the one hand, he had to position Polk and the Tennessee delegation as loyal to Van Buren, but without alienating other factions, to maximize Polk's chances for the vice-presidential nomination. On the other hand, he had to develop and implement a strategy to bring Polk forward as a possible compromise candidate for the presidency itself – something that had never been done before at that point – again, without raising the ire of other party leaders and their factions.

In fact, Pillow accomplished these goals with great skill. As the convention moved toward deadlock between Van Buren and Cass, Pillow kept the fractious Tennessee delegates solidly in line behind Van Buren At the same time, Pillow carefully buttonholed key leaders to suggest Polk as the solution. Working primarily through Massachusetts delegate George Bancroft and New Hampshire delegates Henry Carroll (editor of the Concord New Hampshire Patriot and State Gazette) and governor Henry Hubbard, Pillow suggested that any movement toward Polk had to be initiated by northern delegates. If a Polk boomlet appeared in the north, then, Pillow indicated, he would see to it that southern delegations joined it.

Pillow put his plan into motion after the seventh ballot. On the eighth ballot, New Hampshire announced its six votes for Polk, and shortly thereafter Massachusetts added seven more. Tennessee declared that it had not come to the convention to press the nomination of its favorite son, but now that it appeared that he had the enthusiastic support of other states it would cast its votes for him as well. By the end of the roll call, Polk had forty-four votes.

And that was enough. The next ballot, the ninth, was also the last. Virginia, which had loyally adhered to Van Buren through eight ballots, announced that it was switching its votes to Polk. Van Buren's lieutenant, Benjamin Franklin Butler of New York (no, not that Benjamin Franklin Butler), then withdrew Van Buren's name from nomination and announced that he would vote for Polk, who fully met, he said, “the Jeffersonian standard of qualification.”

When all but one of New York's thirty-six delegates also went for Polk, the rush was on. One after another, delegation leaders rose to cast full delegation support to James K. Polk, often adding warm praise for the man or directing piquant invective at Henry Clay [the Whig nominee]. By the time it was over, around two o'clock in the afternoon [on Friday May 31, 1844], every delegate had cast his vote for James Polk, and the Tennessean was declared the unanimous choice of the Democratic convention.

About the illustration:

American general Gideon J. Pillow's self-promoting attempts to discredit Mexican War commander Gen. Winfield Scott are ridiculed in this portrayal of Scott puncturing "Polk's Patent" pillow. Pillow's efforts were widely viewed as part of a campaign by the Polk administration to damage Scott's growing prestige at home. An anonymous letter--actually written by Pillow--published in the "New Orleans Delta" on September 10, 1847, and signed "Leonidas," wrongfully credited Pillow for recent American victories at Churubusco and Contreras. The battles were actually won by Scott. When Pillow's intrigue was exposed, he was arrested by Scott and held for a court-martial. Polk, defensive of Pillow, recalled Scott to Washington. During the trial that ensued, "Delta" correspondent James L. Freaner testified in Scott's favor. At Pillow's behest Maj. Archibald W. Burns, a paymaster, claimed authorship of the "Leonidas" letter. Currier's cartoon was probably published during or shortly after Pillow's trial, which began in March 1848. With the sword of "Truth," Scott (right) punctures a pillow held by Burns (left) and which is being inflated by Pillow (kneeling, center). Scott holds Freaner's testimony in his hand and treads on the Leonidas letter. He exclaims at the air released, "Heavens what a smell!" At left, behind Burns is a strong box on which rests a sack of coins, marked "From Genl. Pillow for fathering the Leonidas Letter."