I have previously published

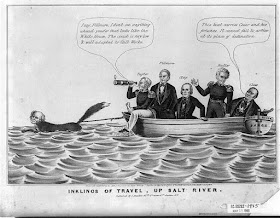

several posts on the 1826 duel held between then Secretary of State

Henry Clay and Virginia Senator

John Randolph of Roanoke. Reading the account of the duel, and the accompanying endnotes, contained in

Henry Clay: The Essential American gives me another excuse to revisit this colorful event.

What I realized when I read the Heidlers' description was that Missouri Senator

Thomas Hart Benton had been a witness to and participant in events leading up to the duel and had witnessed the duel itself. What is more, Benton composed a description of those events, published in his autobiography.

I located an 1858 printing of Benton's autobiography,

Thirty Years' View; or, A History of the Working of the American Government for Thirty Years, From 1820 to 1850 (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1858), at Google Books. It turns out that Benton's description of the duel is detailed to the point of being turgid. I therefore thought that I'd highlight a few angles that I think are particularly interesting.

On Saturday April 1, 1826, Randolph approached Benton and asked him whether he “was a blood-relation of Mrs. Clay.” Benton said he was (Mrs. Clay's maiden name had been

Lucretia Hart). Randolph “immediately replied that that put an end to a request which he had wished to make of me.” He then proceeded to explain that he had received and accepted a challenge from Clay and was hoping that Benton would be his second. Since Benton could not serve, Randolph would ask Col.

Edward F. Tattnall (spelled "Tatnall" throughout Benton's account) to do so.

Then Randolph told Benton a secret and swore him to silence: he would not fire on Clay:

Before leaving, he told me he would make my bosom the depository of a secret which he should commit to no other person: it was, that he did not intend to fire at Mr. Clay. He told it to me because he wanted a witness of his intention, and did not mean to tell it to his second or any body else; and enjoined inviolable secrecy until the duel was over.

Procedural details and efforts by the seconds to dissuade the participants delayed matters for a week, but the duel was at last scheduled to take place on Saturday April 8th at 4:00 p.m. The location was the Virginia side of the Potomac, selected by Randolph because, if shot, his native state was “his chosen ground to receive his blood.”

That morning, Benton met with Randolph, hoping to obtain a reaffirmation of his commitment not to fire at Clay. Afraid to ask Randolph directly (because Randolph might take a direct question as an affront to his honor), Benton hit upon a scheme to elicit the information indirectly. He related to Randolph that he had visited the Clay residence the evening before and encountered a pathetic scene. The youngest Clay boy was sleeping on the sofa. Although apparently unaware of the impending duel, Mrs. Clay was “the picture of desolation.” Always physically frail, she was still despondent over the recent deaths of two daughters. “I told him of my visit to Mr. Clay the night before – of the late sitting – the child asleep – the unconscious tranquillity of Mrs. Clay; and added, I could not help reflecting how different all that might be the next night.”

Randolph understood and gave Benton the reassurance he was hoping for. “He understood me perfectly, and immediately said, with a quietude of look and expression which seemed to rebuke an unworthy doubt, 'I shall do nothing to disturb the sleep of the child or the repose of the mother.'"

Immediately before the duel, however, two events occurred that caused Randolph to question his resolve. First, Randolph became flustered when he dropped his pistol on the dueling ground, causing it to discharge. More importantly, shortly before that, during his carriage ride to the dueling ground, he had learned that Clay had requested a change in the rules that made his (Randolph's) injury or death more likely.

The duel was to be with pistols at ten paces, and the seconds had agreed to a procedure that minimized the likelihood that either participant would be shot. Immediately after the command to “fire,” there would be a quick count, “One, two, three, stop.” Hopefully, the participants, neither of whom was experienced with firearms, would not have time to raise their pistols and make accurate shots before the “stop” order was recited.

Shortly before the duel, however, Clay's second, Thomas J. Jesup, at Clay's request, asked Randolph's second to agree to slow down the count. Apparently Clay was concerned that, because he had no experience with pistols, he would not even have time to raise his pistol, leaving him defenseless if Randolph was able to get off a shot. Randolph's second declined the request, and the procedure was not changed.

Word of the request got back to Randolph, who apparently believed that the procedure had in fact been altered to slow down the count. Randolph decided that he might fire at Clay, but only to “disable” him. As he wrote in a note shortly before the duel:

"Information received from Col. Tatnall [Randolph's second] since I got into the carriage may induce me to change my mind, of not returning Mr. Clay's fire. I seek not his death. I would not have his blood upon my hands – it will not be upon my soul if shed in self-defence – for the world. He has determined, by the use of a long, preparatory caution by words, to get time to kill me. May I not, then, disable him? Yes, if I please."

When the time came, Randolph did indeed fire at Clay. “Mr. Randolph's bullet struck the stump behind Mr. Clay.” Clay's bullet was likewise wide of its mark.

After the first shots were exchanged, Benton pulled Randolph aside to try to settle the affair. During that conversation, Randolph affirmed that he had aimed only to disable Clay:

[H]e declared to me that he had not aimed at the life of Mr. Clay; that he did not level as high as the knees – not higher than the knee-band; "for it was no mercy to shoot a man in the knee;” that his only object was to disable him and spoil his aim. And then added, with a beauty of expression and a depth of feeling which no studied oratory can ever attain, and which I shall never forget, these impressive words: "I would not have seen him fall mortally, or even doubtfully wounded, for all the land that is watered by the King of Floods and all his tributary streams."

Clay and Randolph had agreed to a second exchange of fire, but Randolph assured Benton that, this time, he would not defend himself. “[Randolph] regretted this fire [his first shot at Clay] the instant it was over. He felt that it had subjected him to imputations from which he knew himself to be free – a desire to kill Mr. Clay, and a contempt for the laws of his beloved State [dueling was illegal in Virginia]; and the annoyances which he felt at these vexatious circumstances revived his original determination, and decided him irrevocably to carry it out.” “He left me to resume his post . . . with the positive declaration that he would not return the next fire."

Randolph was true to his word. Benton recounts the famous climax:

I withdrew a little way into the woods, and kept my eyes fixed on Mr. Randolph, who I then knew to be the only one in danger. I saw him receive the fire of Mr. Clay, saw the gravel knocked up in the same place, saw Mr. Randolph raise his pistol – discharge it in the air; heard him say, “I do not fire at you, Mr. Clay;” and immediately advancing and offering his hand. He was met in the same spirit. They met half way. shook hands, Mr. Randolph saying, jocosely, “You owe me a coat, Mr. Clay" - (the bullet had passed through the skirt of the coat, very near the hip) – to which Mr. Clay promptly and happily replied, "I am glad the debt is no greater."