Benjamin “Beast” Butler was not a great officer, but he did amass some notoriety during the war by, among other things, authorizing Union troops to treat women in New Orleans as prostitutes (which earned him that “Beast” designation) and later getting “bottled up” in the Bermuda Hundred. Most of all, he acquired some fame as the first Union officer who refused to return to their masters slaves who escaped to Union lines, on the theory that they were “contraband property of war.”

James Oakes book Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 is a delight, not least for his recounting of incidents such as the circumstances under which Butler, having been exiled by Winfield Scott to Fortress Monroe at Hampton Roads, made and sought approval for his decision in May 1861. But I enjoyed even more Oakes’ brief recap of Butler’s pre-war biography, which made him the most unlikely of liberators. A military wannabe who was unable to secure an appointment to West Point, Butler instead became a lawyer and Democratic politician in Massachusetts. In the late 1840s and early 1850s Butler flirted with Free Soil Democrats and Conscience Whigs, but later in the decade he returned to his Democratic roots, going so far as to support John Breckinridge for president in 1860:

Rather than embrace the new antislavery Republican Party, Butler went back to the Democrats. He campaigned for James Buchanan in 1856, endorsed the proslavery Lecompton Constitution for Kansas, supported the Dred Scott decision, and appealed to white workers with racial demagoguery. At his party’s tumultuous 1860 nominating convention in Charleston, South Carolina, Butler voted more than fifty times for Jefferson Davis and ended up supporting John Breckinridge, the proslavery Democrat. Butler even apologized for having once flirted with the Free Soil Party. The best that can be said of Butler’s antislavery record is that it was unimpressive.

As Oakes goes on to explain, secession and Fort Sumter – coupled, perhaps, with the opportunity to realize his long-suppressed dreams of a military career – turned Butler around. And having acquired the opportunity, Butler, although no great military man, was smart enough to understand the logic of war, and of the Republican Party:

[P]roperty of whatever nature, used or capable of being used for warlike purposes, and especially when being so used, may be captured and held either on sea or on shore as property contraband of war.

About the illustration at the top of the post, entitled The (Fort) Monroe Doctrine (1861):

On May 27, 1861, Benjamin Butler, commander of the Union army in Virginia and North Carolina, decreed that slaves who fled to Union lines were legitimate "contraband of war," and were not subject to return to their Confederate owners. The declaration precipitated scores of escapes to Union lines around Fortress Monroe, Butler's headquarters in Virginia. In this crudely drawn caricature, a slave stands before the Union fort taunting his plantation master. The planter (right) waves his whip and cries, "Come back you black rascal." The slave replies, "Can't come back nohow massa Dis chile's contraban." Hordes of other slaves are seen leaving the fields and heading toward the fort.

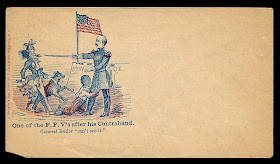

The second image is a pictorial envelope. The figure says, "By golly massa Butler, I like dis better dan workin' in de field for ole Sesesh massa."

The third image is also a pictorial envelope, entitled Contraband of War; or, Volunteer Sappers and Miners From the "F.F.V." shows "African-American men with mining tools in-hand, volunteering to join the Union Army." The figures say, "Massa Butler, we's jest seceed from de 'meen-asses junction,' and wants to 'list in the counterband regiment. We's no great hands at fightin' , but we kin run 'most as fast as our old massas did toder night, Now, ef you wants any trenches or forti'cations made, we's de niggers to call upon in dat ar line." "F.F.V." seems to refer to First Families of Virginia.

In the fourth image, an "African-American boy clings to the leg of General Butler. Butler extends his sword to fend-off slave owner with whip and dog." General Butler says, "can't see it."

The fifth image is an 1861 print on an envelope that

shows a slave at the Union fort taunting his plantation master. The planter (left) waves his whip and cries, "Come back you black rascal." The slave replies, "Can't come back nohow massa Dis chile's contraban." Other slaves are seen leaving the fields and heading toward the fort. On May 27, 1861, Benjamin Butler, commander of the Union army in Virginia and North Carolina, decreed that slaves who fled to Union lines were legitimate "contraband of war," and were not subject to return to their Confederate owners. The declaration precipitated scores of escapes to Union lines around Fortress Monroe,