Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 - c. 325) was a rhetorician from North Africa who became a convert to Christianity. I recently ran across Lactantius' De Mortibus Persecutorum, which has got to be one of the stranger works ever written. As the title suggests ("On the Deaths of the Persecutors"), the work concerns itself with the manner in which various persecutors of Christians died. What the title does not convey is the glee with which Lanctantius recounts the stories he relates.

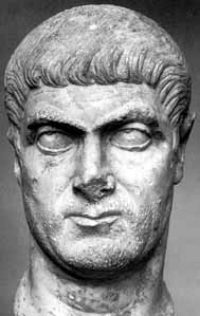

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 - c. 325) was a rhetorician from North Africa who became a convert to Christianity. I recently ran across Lactantius' De Mortibus Persecutorum, which has got to be one of the stranger works ever written. As the title suggests ("On the Deaths of the Persecutors"), the work concerns itself with the manner in which various persecutors of Christians died. What the title does not convey is the glee with which Lanctantius recounts the stories he relates.In the 280s and 290s, the Emperor Diocletian realized that the Roman Empire was too big for any one man. In order to address this, as well as the secession problem, which had bedeviled the Empire from its inception, Diocletian created the Tetrarchy. He appointed a trusted general, Maximian, as co-ruler, bearing the title Augustus. The two Augusti then appointed sub-emperors, titled Caesari. Diocletian appointed as his Caesar the general Galerius (full name Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus). (Maximian appointed as his Caesar Constantius, the father of Constantine the Great.)

In 305, Diocletian and Maximian retired as Augusti. and Galerius and Constantius moved up and became the new Augusti, or co-emperors. The latter, in turn, appointed new Caesari. Diocletian and Galerius were primarily responsible for the eastern half of the Empire. Maximian and Constantius were primarily responsible for the western part.

Meanwhile, beginning in 303, what Chistians call the "great persecution" began. In fact, the vigor with which Christians were persecuted varied greatly in different parts of the empire. Galerius seems to have been the only one of the four tetrarchs who pursued the persecution with unrestrained zeal. As a result, Galerius became despised by Christians in general, and by Lactantius in particular.

Galerius died in the year 311. Scholars have speculated that it was some form of bowel cancer. Whatever it was, Lactantius described the progression of the disease with gleeful delight:

And now, when Galerius was in the eighteenth year of his reign, God struck him with an incurable plague. A malignant ulcer formed itself low down in his secret parts, and spread by degrees. The physicians attempted to eradicate it, and healed up the place affected. But the sore, after having been skinned over, broke out again; a vein burst, and the blood flowed in such quantity as to endanger his life. The blood, however, was stopped, although with difficulty. The physicians had to undertake their operations anew, and at length they cicatrized the wound. In consequence of some slight motion of his body, Galerius received a hurt, and the blood streamed more abundantly than before. He grew emaciated, pallid, and feeble, and the bleeding then stanched. The ulcer began to be insensible to the remedies applied, and a gangrene seized all the neighbouring parts. It diffused itself the wider the more the corrupted flesh was cut away, and everything employed as the means of cure served but to aggravate the disease.

“The masters of the healing art withdrew.”

Then famous physicians were brought in from all quarters; but no human means had any success. Apollo and Æsculapius were besought importunately for remedies: Apollo did prescribe, and the distemper augmented. Already approaching to its deadly crisis, it had occupied the lower regions of his body: his bowels came out, and his whole seat putrefied. The luckless physicians, although without hope of overcoming the malady, ceased not to apply fomentations and administer medicines. The humours having been repelled, the distemper attacked his intestines, and worms were generated in his body. The stench was so foul as to pervade not only the palace, but even the whole city; and no wonder, for by that time the passages from his bladder and bowels, having been devoured by the worms, became indiscriminate, and his body, with intolerable anguish, was dissolved into one mass of corruption.

“Stung to the soul, he bellowed with the pain,

So roars the wounded bull.”

They applied warm flesh of animals to the chief seat of the disease, that the warmth might draw out those minute worms; and accordingly, when the dressings were removed, there issued forth an innumerable swarm: nevertheless the prolific disease had hatched swarms much more abundant to prey upon and consume his intestines. Already, through a complication of distempers, the different parts of his body had lost their natural form: the superior part was dry, meagre, and haggard, and his ghastly-looking skin had settled itself deep amongst his bones while the inferior, distended like bladders, retained no appearance of joints. These things happened in the course of a complete year; and at length, overcome by calamities, he was obliged to acknowledge God, and he cried aloud, in the intervals of raging pain, that he would re-edify the Church which he had demolished, and make atonement for his misdeeds; and when he was near his end, he published an edict of the tenor following [the edict in effect decriminalized Christianity].

Galerius, however, did not, by publication of this edict, obtain the divine forgiveness. In a few days after he was consumed by the horrible disease that had brought on an universal putrefaction.

No comments:

Post a Comment