Sorry, but I have an irresistible urge to dump on

James Buchanan a little. I did say something nice about Old Buck

once or

twice, but the truth is that it's a whole lot easier and more fun to abuse him. Can you say, "Low hanging fruit"?

This installment dates to fairly early in Buchanan's career, 1827, when Buck was a member of the House of Representatives. But before I get to Buck, I need to give you some background.

The background is the famous

“corrupt bargain” of 1825. In the run-up to the presidential election of 1824 there were four or five contenders.

John C. Calhoun dropped out early in 1824, swamped by enthusiasm for Andrew Jackson in Pennsylvania. In the fall elections, none of the remaining four candidates obtained a majority of electoral votes. This meant that, under the

Twelfth Amendment, the trailing candidate, Speaker of the House

Henry Clay, dropped from contention. The remaining three –

John Quincy Adams,

William H. Crawford of Georgia and

Andrew Jackson – advanced to the final round. The winner would be selected by the House of Representatives, with each state's delegation voting as a unit and getting one vote. A majority of state delegations (13 of 24) was required to declare a winner.

This isn't the place to go into gory detail about the alleged “corrupt bargain”. Suffice it to say that Clay used his influence as Speaker of the House to help convince the delegations of three states that he had won and in which Jackson had finished second (Kentucky, Missouri and Ohio) to vote for

“Quinzy”. Adams prevailed with a bare majority of 13 state delegations (Jackson had 7, Crawford 4). Thereafter Adams nominated Clay as his Secretary of State, a position then regarded as the principal stepping-stone to the presidency. Jackson and his supporters cried foul, maintaining that Adams had gained office only by entering into a “corrupt bargain” with Clay.

Over two years later, on March 27, 1827, the Jacksonian storyline took an odd twist that appeared both to enhance the credibility of an explicit “bargain” and to emphasize the incorruptibility of Old Hickory. On that date, the Fayetteville

Carolina Observer published a letter by Virginia planter Carter Beverley asserting that Clay's friends had approached Jackson with a deal before Clay sealed his corrupt bargain with Adams. In a nutshell, Clay had offered to make the Old Hero president if he agreed

not to make Adams his Secretary of State. Old Hickory had virtuously and indignantly rejected the offer.

The wonderful

James Parton quotes extensively from Beverly's letter in the

third volume of his Life of Jackson (paragraph breaks added):

I have just returned from General Jackson's. I found a crowd of company with him. Seven Virginians were of the number. He gave me a most friendly reception, and urged me to stay some days longer with him.

He told me this morning, before all his company, in reply to a question that I put to him concerning the election of J. Q. Adams to the presidency, that Mr. Clay's friends made a proposition to his friends, that, if they would promise, for him [General Jackson] not to put Mr. Adams into the seat of Secretary of State, Mr. Clay and his friends would, in one hour, make him [Jackson] the President.

He [General Jackson] most indignantly rejected the proposition, and declared he would not compromise himself; and unless most openly and fairly made the President by Congress, he would never receive it. He declared, that he said to them, he would see the whole earth sink under them, before he would 'bargain or intrigue for it.'"

Jacksonian newspaper editors knew a good thing when they saw it.

Duff Green, a cohort of John Calhoun and Jackson (who were at this point allied), promptly republished the story and charge in his United States

Telegraph.

Clay denied the story but otherwise bided his time. Soon enough, Jackson fell into the trap by writing a letter, made public on June 5, 1827, endorsing and elaborating on Beverley's story. Among other things, Jackson revealed that he had been informed of Clay's offer by “a member of Congress of high respectability.” James Parton again quotes from letter (paragraph breaks added):

Early in January, 1825, a member of Congress, of high respectability, visited me one morning, and observed that he had a communication he was desirous to make to me; that he was informed there was a great intrigue going on, and that it was right I should be informed of it; that he came as a friend, and let me receive the communication as I might, the friendly motives through which it was made he hoped would prevent any change of friendship or feeling in regard to him. To which I replied, from his high standing as a gentleman and member of Congress, and from his uniform friendly and gentlemanly conduct toward myself, I could not suppose he would make any communication to me which he supposed was improper. Therefore, his motives being pure, let me think as I might of the communication, my feelings toward him would remain unaltered.

The gentleman proceeded: He said he had been informed by the friends of Mr. Clay, that the friends of Mr. Adams had made overtures to them, saying, if Mr. Clay and his friends would unite in aid of Mr. Adams' election, Mr. Clay should be Secretary of State; that the friends of Mr. Adams were urging, as a reason to induce the friends of Mr. Clay to accede to their proposition, that if I were elected President, Mr. Adams would be continued Secretary of State (innuendo, there would be no room for Kentucky); that the friends of Mr. Clay stated, the West did not wish to separate from the West, and if I would say, or permit any of my confidential friends to say, that in case I were elected President, Mr. Adams should not be continued Secretary of State, by a complete union of Mr. Clay and his friends, they would put an end to the presidential contest in one hour. And he was of opinion it was right to fight such intriguers with their own, weapons.

To which, in substance, I replied – that in politics, as in every thing else, my guide was principle; and contrary to the expressed and unbiased will of the people, I never would step into the presidential chair; and requested him to say to Mr. Clay and his friends (for I did suppose he had come from Mr. Clay, although he used the term of' Mr. Clay's friends) that before I would reach the presidential chair by such means of bargain and corruption, I would see the earth open and swallow both Mr. Clay and his friends, and myself with them. If they had not confidence in me to believe, if I were elected, that I would call to my aid in the cabinet men of the first virtue, talent, and integrity, not to vote for me.

The second day after this communication and reply, it was announced in the newspapers that Mr. Clay had come out openly and avowedly in favor of Mr. Adams. It may be proper to observe, that, on the supposition that Mr. Clay was not privy to the proposition stated, I may have done injustice to him. If so, the gentleman informing me can explain.

Clay then pounced. He again publicly denied the report and this time also demanded that Jackson reveal the identity of the “member of Congress of high respectability” who had served as the source. “'I demand the witness,' he thundered [according to

Robert Remini], 'and await the event with fearless confidence.'”

You can probably see where this is going. It soon came out that the source was none other than Jacksonian Congressman James Buchanan of Pennsylvania. The only problem was that Buchanan's story was untrue.

Caught between a rock and a hard place, Buchanan issued a public letter, printed in the Lancaster

Journal on August 6, 1827, in which he asserted that the whole thing had been a misunderstanding. Jackson, he suggested, had misinterpreted statements that Buchanan had made to him in a conversation held at the very end of 1824. Parton quotes from Buchanan's letter (paragraph breaks added):

The duty which I owe to the public, and to myself, now compels me to publish to the world the only conversation which I ever held with General Jackson, upon the subject of the last presidential election, prior to its termination. . . .

On the 30th of December, 1824, (I am able to fix the time, not only from my own recollection, but from letters which I wrote on that day, on the day following, and on the 2d of January, 1825,) I called upon General Jackson. After the company had left him, by which I found him surrounded, he asked me to take a walk with him; and, while we were walking together upon the street, I introduced the subject. I told him I wished to ask him a question in relation to the presidential election; that I knew he was unwilling to converse upon the subject; that, therefore, if he deemed the question improper, he might refuse to give it an answer: that my only motive in asking it, was friendship for him, and I trusted he would excuse me for thus introducing a subject about which I knew he wished to be silent. His reply was complimentary to myself, and accompanied with a request that I would proceed.

I then stated to him there was a report in circulation, that he had determined he would appoint Mr. Adams Secretary of State, in case he were elected President, and that I wished to ascertain from him whether he had ever intimated such an intention; that he must at once perceive how injurious to his election such a report might be; that no doubt there were several able and ambitious men in the country, among whom I thought Mr. Clay might be included, who were aspiring to that office; and, if it were believed he had already determined to appoint his chief competitor, it might have a most unhappy effect upon their exertions, and those of their friends; that, unless he had so determined, I thought this report should be promptly contradicted under his own authority. I mentioned it had already probably done him some injury. . . .

After I had finished, the General declared he had not the least objection to answer my question; that he thought well of Mr. Adams, but he never said or intimated that he would, or would not, appoint him Secretary of State; that these were secrets he would keep to himself – he would conceal them from the very hairs of his head; that if he believed his right hand then knew what his left would do on the subject of appointments to office, he would cut it off and cast it into the fire; that if he ever should be elected President, it would be without solicitation, and without intrigue, on his part; that he would then go into office perfectly free and untrammeled, and would be left at perfect liberty to fill the offices of the government with the men whom, at the time, he believed to be the ablest and the best in the country.

I told him that this answer to my question was such a one as I had expected to receive, if he answered it at all; and that I had not sought to obtain it for my own satisfaction. I then asked him if I were at liberty to repeat bis answer? He said that I was at perfect liberty to do so, to any person I thought proper. I need scarcely remark that I afterward availed myself of the privilege.

The conversation on this topic here ended, and in all our intercourse since, whether personally, or in the course of our correspondence, General Jackson never once adverted to the subject, prior to the date of his letter to Mr. Beverly. I called upon General Jackson, upon the occasion which I have mentioned, solely as his friend, upon my individual responsibility, and not as the agent of Mr. Clay or any other person.

“Mortified by the testimony of his Pennsylvania friend [says

Merrill Peterson], Jackson retired from the controversy without another word.” Privately, however, he was, in the words of Robert Remini, “livid over the Buchanan letter. 'The outrageous statements of Mr. Buchanan will require my attention,' he rumbled to his friend and neighbor

William B. Lewis.”

James Parton quotes extensively from Jackson's letter to Lewis (or perhaps a second letter to him). Jackson seems to have believed both that Buchanan's 1825 (or 1824) inquiry to him was “corrupt[]” and that his 1827 letter describing the conversation was a lie (once again, paragraph breaks added):

Your observations with regard to Mr. Buchanan are correct. He showed a want of moral courage in the affair of the intrigue of Adams and Clay – did not do me justice in the expose he then made, and I am sure about that time did believe there was a perfect understanding between Adams and Clay about the presidency and the Secretary of State. This I am sure of. But whether he viewed that there was any corruption in the case or not, I know not; but one thing I do know, that he wished me to combat them, with their own weapons – that was, let my friends say if I was elected I would make Mr. Clay Secretary of State. This, to me, appeared deep corruption, and I repelled it with that honest indignation as I thought it deserved.

Buchanan, for his part, could only grovel. Remini again: “Meanwhile, the hapless meddler apologized for misleading the general. 'I regret beyond expression,' he wrote, 'that you believed me to be an emissary of Mr. Clay.'”

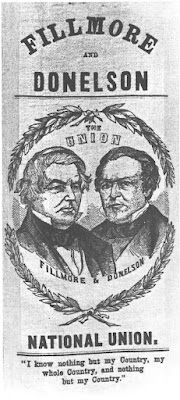

The illustration is taken from

The Wasp's Stuff. Excellent!