J.L. Bell at Boston 1775 had a post that alerted me to the fact that the Massachusetts Historical Society has made the complete John Quincy Adams diaries available online. It's a wonderful resource that is, at the same time, completely maddening. The pages are digitized photos of the original diaries. Being able to see and read Adams's actual writing is awe inspiring. At the same time, the format means that the 14,000 pages (!) of diaries are not word searchable.

That's OK. The thing that has driven me crazy is the size of the images. The regular pages are too small to read, and the "pop up large images" are too large -- to read each line, you have to scroll across the page, then scroll back to pick up the next line. As a result, I tend to lose the lines. I tried printing out a page using the "printer friendly page" version, but that, too, is too small. The size of the text is reduced in order to accommodate annoying copyright and source information at the top and bottom of the page.

All this means that it's impossible for these old eyes to read more than de minimis amounts of the text without going blind.

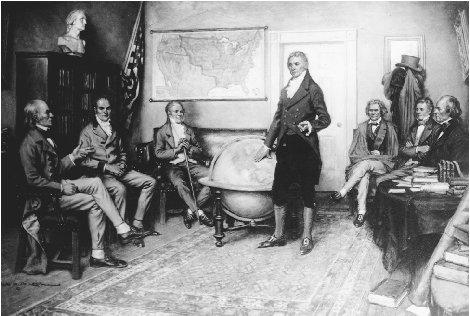

Despite -- or because of -- these limitations, I decided to try to find a single specific entry: Adams's description of the cabinet meeting at which President Monroe asked the members of his cabinet for their opinions on whether the Missouri Compromise Bill was constitutional. I knew, from other sources, that the meeting took place on Friday March 3, 1820. The diaries are date searchable, so I put in the date and found the relevant entry in short order.

The description of the meeting begins at page 276 of Diary 31. I had expected it to be relatively short, if only because I assumed that Adams would not have had the time to go on at length. How wrong I was.

Here is the core of the entry. Since I've about gone blind, I will post the remainder after my eyes recover. In order to make the description more readable, I have added paragraph divisions; none exist in the original. I have also added some links to the names that appear, even though anyone who reads this will almost certainly know who the characters are. Here goes:

That's OK. The thing that has driven me crazy is the size of the images. The regular pages are too small to read, and the "pop up large images" are too large -- to read each line, you have to scroll across the page, then scroll back to pick up the next line. As a result, I tend to lose the lines. I tried printing out a page using the "printer friendly page" version, but that, too, is too small. The size of the text is reduced in order to accommodate annoying copyright and source information at the top and bottom of the page.

All this means that it's impossible for these old eyes to read more than de minimis amounts of the text without going blind.

Despite -- or because of -- these limitations, I decided to try to find a single specific entry: Adams's description of the cabinet meeting at which President Monroe asked the members of his cabinet for their opinions on whether the Missouri Compromise Bill was constitutional. I knew, from other sources, that the meeting took place on Friday March 3, 1820. The diaries are date searchable, so I put in the date and found the relevant entry in short order.

The description of the meeting begins at page 276 of Diary 31. I had expected it to be relatively short, if only because I assumed that Adams would not have had the time to go on at length. How wrong I was.

Here is the core of the entry. Since I've about gone blind, I will post the remainder after my eyes recover. In order to make the description more readable, I have added paragraph divisions; none exist in the original. I have also added some links to the names that appear, even though anyone who reads this will almost certainly know who the characters are. Here goes:

When I came this day to my office, I found there a Note requesting me to call at one O’Clock at the President’s house. It was then one, and I immediately went over. He expected that the two bills, for the admission of Maine, and to enable Missouri to make a constitution, would have been brought to him for signature, and he had questioned all the members of the Administration to ask their opinions in writing to be deposited in the Department of State, upon two questions. 1. Whether Congress had a Constitutional right to prohibit Slavery in a Territory? and 2. Whether the 8th Section of the Missouri Bill (which interdicts Slavery forever in the Territory North of 36 1/3 Latitude, was applicable only to the territorial state, or would extend to it after it should become a State.

As to the first question, it was unanimously agreed that Congress have the power to prohibit Slavery in the Territories, and yet neither, Crawford, Calhoun, nor Wirt could find any express power to that effect given in the Constitution, and Wirt declared himself very decidedly against the admission of any implied powers.

The progress of this discussion has so totally merged in passion all the reasoning faculties of the Slave holders, that these Gentlemen in the simplicity of their hearts had come to a conclusion in direction opposition to their premises, without being aware or conscious of inconsistency – They insisted upon it that the clause in the Constitution, which gives Congress power to dispose of, and make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory and other property of the United States, had reference to it, only as land, and conferred no authority to make rules, binding upon its inhabitants; and Wirt added the notable Virginian objection, that Congress could make only needful rules and regulations – and that a prohibition of Slavery was not needful. Their argument, as Randolph said of it in the House covered the whole ground, and their compromise, measured by their own principles is a sacrifice of what they hold to be the Constitution.

I had no doubt of the right of Congress to interdict Slavery in the Territories and urged that the power contained in the term dispose of, included the authority to do every thing that could be done with it as mere property, and that the additional words authorizing needful rules and regulations respecting it, must have reference to persons connected with it, or could have no meaning at all. As to the force of the term needful, I observed it was relative, and must always be supposed to have reference to some end – needful to what end – needful in the Constitution of the United States to any of the ends for which that compact was formed. Those ends are declared in its preamble – to establish justice for example. What can be more needful to the establishment of Justice than the interdiction of Slavery where it does not exist.

As to the second question my opinion was the interdiction of slavery in the 8th Section of the Bill, forever, would apply and be binding upon the States, as well as upon the Territory; because by its interdiction in the Territory, the People when they come to form a Constitution would have no right to sanction Slavery – Crawford said that in the new States, which have been admitted into the Union upon the express condition that their Constitutions should consist with the perpetual interdiction of Slavery, it might be sanctioned by an ordinary act of their Legislatures – I said, that whatever a State Legislature might do in point of fact, they could not by any rightful exercise of power establish Slavery – The Declaration of Independence not only asserts the natural equality of all men, and their inalienable right to Liberty; but that the only just powers of government are derived from the consent of the governed. A power for one part of the people to make Slaves of the other can never be derived from consent, and is therefore not a just power.

Crawford said this was the opinion that had been attributed to Mr. King. I said it was undoubtedly the opinion of Mr. King; and it was mine. I did not want to make a public display of it, where it might excite irritation, but if called upon officially for it, I should not withhold it. But the opinion was not peculiar to Mr. King and me – it was an opinion universal in the States where there are no Slaves. It was the opinion of all those members of Congress who voted for the restriction upon Missouri, and of many of those who voted against it – As to the right of imposing the restriction upon a State, the President had signed a Bill with precisely such a restriction upon the State of Illinois – Why should the question be made now, which was not made then – Crawford said that was done in conformity to the compact of the Ordinance of 1787: and besides the restriction was a nullity, not binding upon the Legislatures of those States.

I did not reply to the assertion that a solemn compact, announced before heaven and earth in the ordinance of 1787, a compact laying the foundation of security to the most sacred rights of human nature, against the most odious of oppressions, a compact solemnly renewed by the act of Congress enabling the States of Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, to form State Governments, and again by the Acts for admitting those States into the Union, was a nullity, which the Legislatures of either of those States may at any time disregard and trample under foot. It was sickening to my Soul to hear the assertion; but to have discussed it there would have been useless, and only have kindled in the bosom of the Executive the same flame which has been raging in Congress; and in the Country – Its discussion was unnecessary to the decision of the questions proposed by the President – I therefore only said that the Ordinance of 1787 had been passed by the old Congress of the Confederation, without authority from the States, but had been tacitly confirmed by the adoption of the present Constitution, and the authority given to Congress in it to make needful rules and regulations for the territory – I added that in one of the numbers of the Federalist, there was an admission that the old Congress had passed the Ordinance without authority, under an impulse of necessity – and that it was used as an argument in favour of the enlarged powers granted to Congress in the Constitution.

Crawford said it could therefore have little or no weight as authority. I replied that it was not wanted as authority – That when the old Confederation was adopted the United States had no territory. Nor was there in the Act of Confederation, in which the powers of Congress under it were enumerated a word about territory. But there was a clause interdicting to Congress the exercise of any powers not expressly given them: I alluded to the origin of the Confederation with our Revolution – To the revolutionary powers exercised by Congress, before the Confederation was adopted – To the question whether the northwestern territory belonged to the United States or the separate States – To the delays occasioned by the question in the acceptance of the Confederation; and to the subsequent cessions of Territory by several States, to the Union, which gave occasion for the ordinance of 1787. To all which Crawford said nothing.

Wirt said that he perfectly agreed with me that there could be no rightful power to establish Slavery where it was res nova – But he thought it would not be the force of the Act of Congress that would lead to this result – The principle itself being correct, though Congress might have no power to prescribe it to a sovereign State. To this my reply was, that the power of establishing Slavery, not being a sovereign power, but a wrongful and despotic power, Congress had a right to say that no State undertaking to establish it de novo should be admitted into the Union; and that a State which should undertake to establish it would put herself out of the pale of the Union, and forfeit all the rights and privileges of the connection.

The President said that it was impossible to exclude the principle of implied powers, being granted to Congress by the Constitution. The Powers of Sovereignty were distributed between the general and the State governments – Extensive powers were given in general terms; all detailed and incidental powers were implied in the general grant. Some years ago, Congress had appropriated a sum of money to the relief of the inhabitants of Caraccas, who had suffered by an earthquake. There was no express grant of authority to apply the public money to such a purpose – It was by an implied power – The material question was only when the power supposed to be implied came in conflict with rights reserved to the State Governments – He inclined also to think with me, that the Rules and Regulations, which Congress were authorized to make for the territories, must be understood as extending to their inhabitants – And he resumed to the history of the Northwestern Territory. The cessions by the several States to the Union, and the controversies concerning this subject during our revolutionary War.

He said he wished the written opinion of the members of the Cabinet, without discussion, in terms as short as it could be expressed, and merely that it might be deposited in the Department of State – I told him that I should prefer a dispensation from answering the second question; especially as I should be alone here in the opinion which I entertained; for Mr. Thompson the Secretary of the Navy cautiously avoided giving any opinion, upon the question of natural right, but assented to the Slave sided doctrine that the eighth Section of the Bill, word forever, and all, applied only to the time and condition of the territorial government – I said therefore that if required to give my opinion upon the second question standing alone, it would be necessary for me to assign the reasons upon which I entertained it – Crawford saw no necessity for any reasoning about it, but had no objection to my assigning my reasons.

Calhoun thought it exceedingly desirable that no such argument should be drawn up and deposited – He therefore suggested to the President, the idea of changing the terms of the second question, so that it should be, whether the 8th Section of the Bill was consistent with the Constitution? which the other members of the administration might answer affirmatively, assigning their reason, because they considered it applicable only to the territorial States; while I could answer it, also affirmatively, without annexing any qualification – To this the President readily assented, and I as readily agreed – The questions are to be framed accordingly.

Nice. Thanks for taxing your eyesight to put it up.

ReplyDelete