Stanton Krauss, a Professor of Law at Quinnipiac University, has published a gem of an article in the Connecticut Law Review on his historical researches relating to one aspect of Justice Taney’s

Dred Scott decision:

New Evidence That Dred Scott Was Wrong About Whether Free Blacks Could Count for the Purposes of Federal Diversity Jurisdiction. Although the article is available on SSRN, and I encourage you to read it for yourself, here is the gist of it.

As you may know, one aspect of the

Dred Scott case turned on whether free blacks were “Citizens” under

Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution, which grants federal courts jurisdiction over “Controversies . . . between Citizens of different States.” Scott had filed his second suit – the one that ultimately reached the Supreme Court – based upon “diversity of citizenship,” as lawyers now generally refer to the principle. In particular, Scott alleged that he was, at the time he filed suit, a citizen of the State of Missouri, and that the defendant, Sanford, was a citizen of the State of New York.

In his

“Opinion of the Court,” Taney, among other things, denied that blacks – even free blacks – were or could ever become “Citizens” within the meaning of Article III, Section 2. Therefore, no diversity of citizenship existed, and federal courts accordingly lacked jurisdiction over the suit.

Although Taney purported to reach his conclusion based on historical inquiry, Professor Krauss points out that that inquiry did not focus on the Founders’ (or the founding generation’s) words or deeds concerning the diversity provision. Rather,

Taney proceeded by asking a far more general (and far more abstract) question: whether the Founders intended to allow free blacks to “become . . . member[s] of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such became entitled to all rights, and privileges, and immunities, guarantied by that instrument to its citizens.”

Not unexpectedly given its phrasing, Taney answered this question in the negative. But what Taney did not do was pose, provide any evidence concerning, or answer the more immediate historical question: was there any evidence as to whether the Founders thought that free blacks could be “Citizens” for purposes of the diversity provision? Nor did the dissenters:

Although Taney’s conclusion was vigorously denounced by Justices Curtis and McLean, neither challenged his failure to adduce any evidence of what the Founders actually thought about the status of free blacks with respect to the diversity provision . . .. And neither the dissenting Justices nor the lawyers for the parties cited any such evidence, on either side of the issue. It’s only fair to assume that no one knew of anything to cite.

Remarkably, Professor Krauss has unearthed a tantalizing piece of evidence on the question – and it suggests that the founding generation believed that free blacks could be “Citizens” for diversity purposes (or perhaps that it did not occur to them that free blacks were

not “Citizens” for that purpose).

Professor Krauss has apparently been engaged for over a decade in a “comprehensive study of early American newspapers and legal manuscripts.” As he describes it, he stumbled across a story about two 1793 federal court cases in which the plaintiff was black and the defendants white. Very briefly (read the article for more detail), Peter Elkay, a free black resident of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, sued John Ives III and Joel Moss, two white residents of Wallingford, Connecticut, for allegedly kidnapping Elkay’s daughters. Invoking diversity jurisdiction, Elkay brought his suits in federal court in Connecticut. The cases were tried in New Haven on April 28, 1793. The jury awarded Elkay damages of $250 in each case, motions to set aside the verdicts were denied, judgments were entered in Elkay’s favor and he was granted execution in that amount.

The lawyers and judges involved in the cases constituted a virtual “who’s who” of outstanding legal talent.

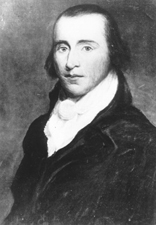

Pierpont Edwards, the first and then-current United States Attorney for the District of Connecticut, represented Elkay. Connecticut Congressman

James Hillhouse represented the defendants. Federal District Judge

Richard Law and Supreme Court Justice

James Wilson presided over the proceedings. All were knowledgeable about the Constitution. Edwards, Hillhouse and Law had all been delegates to the convention at which Connecticut had ratified the Constitution. Wilson, of course, was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention itself and to the Pennsylvania convention that ratified the Constitution on behalf of that state.

During May 1893, reports of the litigation “appeared in almost one-third of the English-language newspapers published in America,” including publications in Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and North Carolina. (Professor Krauss did not find articles on the cases in publications in Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, South Carolina or Georgia.)

During the case, none of the lawyers or judges questioned the diversity jurisdiction issue. After the case, so far as Professor Krauss can tell, no one who read the article about the cases appears to have raised, commented on or complained about the court’s jurisdiction, either in public (letters to newspapers, broadsides, etc.) or in private correspondence.

Professor Krauss dutifully explores other possibilities and concedes that other hypotheses cannot be excluded, but the fair inference is that it did not occur to anyone at the time that Elkay’s status as a free black excluded him from being considered a “Citizen” for purposes of Article III.