Willie and Salome. Ignore the underwear.

History (Mostly Antebellum America), Law, Music (from Classical to Frank Zappa -- are they the same?) and More

The other day, I commented on an excellent American history/civics quiz.

The other day, I commented on an excellent American history/civics quiz.A professor of American history at Columbia University, Eric Foner, said that a multiple-choice exam testing factual knowledge of history could exaggerate student ignorance of American history.

"The study of history has changed enormously," Mr. Foner said. "It's become much more broad and diverse. The study of facts about particular battles has diminished, but maybe students are in a better position to answer questions about the abolition of slavery."

Mr. [CHARLES] PINKNEY moved "that the National Legislature shd. have authority to negative all laws which they shd. judge to be improper." He urged that such a universality of the power was indispensably necessary to render it effectual; that the States must be kept in due subordination to the nation; that if the States were left to act of themselves in any case, it wd. be impossible to defend the national prerogatives, however extensive they might be on paper; that the acts of Congress had been defeated by this means; nor had foreign treaties escaped repeated violations; that this universal negative was in fact the corner stone of an efficient national Govt.; that under the British Govt. the negative of the Crown had been found beneficial, and the States are more one nation now, than the Colonies were then.

Mr. MADISON seconded the motion. He could not but regard an indefinite power to negative legislative acts of the States as absolutely necessary to a perfect system. Experience had evinced a constant tendency in the States to encroach on the federal authority; to violate national Treaties; to infringe the rights & interests of each other; to oppress the weaker party within their respective jurisdictions.

A negative was the mildest expedient that could be devised for preventing these mischiefs. The existence of such a check would prevent attempts to commit them. Should no such precaution be engrafted, the only remedy wd. lie in an appeal to coercion. Was such a remedy eligible? was it practicable? Could the national resources, if exerted to the utmost enforce a national decree agst. Massts. abetted perhaps by several of her neighbours? It wd. not be possible. A small proportion of the Community, in a compact situation, acting on the defensive, and at one of its extremities might at any time bid defiance to the National authority. Any Govt. for the U. States formed on the supposed practicability of using force agst. the unconstitutional proceedings of the States, wd. prove as visionary & fallacious as the Govt. of Congs.

The negative wd. render the use of force unnecessary. The States cd. of themselves then pass no operative act, any more than one branch of a Legislature where there are two branches, can proceed without the other. But in order to give the negative this efficacy, it must extend to all cases. A discrimination wd. only be a fresh source of contention between the two authorities. In a word, to recur to the illustrations borrowed from the planetary system. This prerogative of the General Govt. is the great pervading principle that must controul the centrifugal tendency of the States; which, without it, will continually fly out of their proper orbits and destroy the order & harmony of the political System.

Resolved That the first Wednesday in Jany next be the day for appointing Electors in the several states, which before the said day shall have ratified the said Constitution; that the first Wednesday in feby next be the day for the electors to assemble in their respective states and vote for a president; And that the first Wednesday in March next be the time and the present seat of Congress the place for commencing proceedings under the said constitution.

Sec. 12. And be it further enacted, that the term of four years for which a President and Vice President shall be elected shall in all cases commence on the fourth day of March next succeeding the day on which the votes of the electors shall have been given.

And if the House of Representatives shall not choose a President whenever the right of choice shall devolve upon them, before the fourth day of March next following, then the Vice-President shall act as President, as in case of the death or other constitutional disability of the President.

1. The Electors shall meet in their respective States and vote by ballot for President and Vice-President, one of whom, at least, shall not be an inhabitant of the same State with themselves; they shall name in their ballots the person voted for as President, and in distinct ballots the person voted for as Vice-President, and of the number of votes for each, which lists they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the seat of the Government of the United States, directed to the President of the Senate; the President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted; The person having the greatest number of votes for President, shall be the President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed . . ..

Sec. 11. And be it further enacted, That the only evidence of a refusal to accept or of a resignation of the office of President or Vice President, shall be an instrument in writing declaring the same, and subscribed by the person refusing to accept or resigning, as the case may be, and delivered into the office of the Secretary of State.

7. Before he enter on the execution of his office, he shall take the following oath or affirmation:

"I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of the President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States."

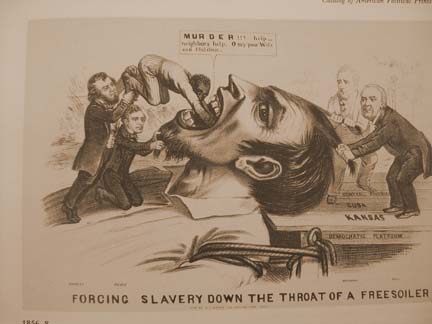

Let’s turn next to President Buchanan’s “legislative history” argument, based on the proceedings at the Constitutional Convention. The president asserted that James Madison’s own position at the Convention supported the conclusion that the federal government did not have the power to suppress statewide secession and insurrection.

Let’s turn next to President Buchanan’s “legislative history” argument, based on the proceedings at the Constitutional Convention. The president asserted that James Madison’s own position at the Convention supported the conclusion that the federal government did not have the power to suppress statewide secession and insurrection. So far from this power [to coerce a State into submission which is attempting to withdraw or has actually withdrawn from the Confederacy] having been delegated to Congress, it was expressly refused by the Convention which framed the Constitution. It appears from the proceedings of that body that on the 31st May, 1787, the clause “authorizing an exertion of the force of the whole against a delinquent State” came up for consideration. Mr. Madison opposed it in a brief but powerful speech, from which I shall extract but a single sentence. He observed:

“The use of force against a State would look more like a declaration of war than an infliction of punishment, and would probably be considered by the party attacked as a dissolution of all previous compacts by which it might be bound.”

Upon his motion the clause was unanimously postponed, and was never, I believe, again presented. Soon afterwards, on the 8th June, 1787, when incidentally adverting to the subject, he said: “Any government for the United States formed on the supposed practicability of using force against the unconstitutional proceedings of the States would prove as visionary and fallacious as the government of Congress,” evidently meaning the then existing Congress of the Confederation.

6. Resolved that each branch ought to possess the right of originating Acts; that the National Legislature ought to be impowered to enjoy the Legislative Rights vested in Congress by the Confederation & moreover to legislate in all cases to which the separate States are incompetent, or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual Legislation; to negative all laws passed by the several States, contravening in the opinion of the National Legislature the articles of Union; and to call forth the force of the Union agst. any member of the Union failing to fulfill its duty under the articles thereof.

The other clauses [of the sixth resolution] giving powers necessary to preserve harmony among the States to negative all State laws contravening in the opinion of the Nat. Leg. the articles of union, down to the last clause, (the words "or any treaties subsisting under the authority of the Union," being added after the words "contravening &c. the articles of the Union," on motion of Dr. FRANKLIN) were agreed to witht. debate or dissent.

The last clause of Resolution 6. authorizing an exertion of the force of the whole agst. a delinquent State came next into consideration.

Mr. MADISON, observed that the more he reflected on the use of force, the more he doubted the practicability, the justice and the efficacy of it when applied to people collectively and not individually. -A union of the States containing such an ingredient seemed to provide for its own destruction. The use of force agst. a State, would look more like a declaration of war, than an infliction of punishment, and would probably be considered by the party attacked as a dissolution of all previous compacts by which it might be bound. He hoped that such a system would be framed as might render this recourse unnecessary, and moved that the clause be postponed. This motion was agreed to nem. con.

Not surprisingly, the Constitution appeared to have solved the problem. Article II required the President to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed" and made him Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces; Article III extended the judicial power of the United States to "cases . . . arising under this Constitution" and other federal laws. Article I empowered Congress to provide for calling out the militia "to execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections, and repel invasions" and to pass all legislation "necessary and proper for carrying into execution" any powers vested by the Constitution "in the Government of the States, or in any department or officer thereof."

If [the question is] answered in the affirmative, it must be on the principle that the power has been conferred upon Congress to declare and to make war against a State. After much serious reflection I have arrived at the conclusion that no such power has been delegated to Congress or to any other department of the Federal Government. It is manifest upon an inspection of the Constitution that this is not among the specific and enumerated powers granted to Congress, and it is equally apparent that its exercise is not "necessary and proper for carrying into execution" any one of these powers."

So far from this power having been delegated to Congress, it was expressly refused by the Convention which framed the Constitution.

It appears from the proceedings of that body that on the 31st May, 1787, the clause "authorizing an exertion of the force of the whole against a delinquent State" came up for consideration. Mr. Madison opposed it in a brief but powerful speech, from which I shall extract but a single sentence. He observed:

"The use of force against a State would look more like a declaration of war than an infliction of punishment, and would probably be considered by the party attacked as a dissolution of all previous compacts by which it might be bound."

Upon his motion the clause was unanimously postponed, and was never, I believe, again presented. Soon afterwards, on the 8th June, 1787, when incidentally adverting to the subject, he said: "Any government for the United States formed on the supposed practicability of using force against the unconstitutional proceedings of the States would prove as visionary and fallacious as the government of Congress," evidently meaning the then existing Congress of the old Confederation.

Without descending to particulars, it may be safely asserted that the power to make war against a State is at variance with the whole spirit and intent of the Constitution. Suppose such a war should result in the conquest of a State; how are we to govern it afterwards? Shall we hold it as a province and govern it by despotic power? In the nature of things, we could not by physical force control the will of the people and compel them to elect Senators and Representatives to Congress and to perform all the other duties depending upon their own volition and required from the free citizens of a free State as a constituent member of the Confederacy.

But if we possessed this power, would it be wise to exercise it under existing circumstances? The object would doubtless be to preserve the Union. War would not only present the most effectual means of destroying it, but would vanish all hope of its peaceable reconstruction. Besides, in the fraternal conflict a vast amount of blood and treasure would be expended, rendering future reconciliation between the States impossible. In the meantime, who can foretell what would be the sufferings and privations of the people during its existence?

The fact is that our Union rests upon public opinion, and can never be cemented by the blood of its citizens shed in civil war. If it can not live in the affections of the people, it must one day perish. Congress possesses many means of preserving it by conciliation, but the sword was not placed in their hand to preserve it by force.

As Chief Justice Marshall said in Osborne v. Bank of the United States [1824], any well-constructed government must have authority to enforce its own laws. The want of such authority was mentioned again and again as one of the leading defects of the Articles of Confederation.

What, in the meantime, is the responsibility and true position of the Executive? He is bound by solemn oath, before God and the country, "to take care that the laws be faithfully executed," and from this obligation he can not be absolved by any human power. But what if the performance of this duty, in whole or in part, has been rendered impracticable by events over which he could have exercised no control? Such at the present moment is the case throughout the State of South Carolina so far as the laws of the United States to secure the administration of justice by means of the Federal judiciary are concerned. All the Federal officers within its limits through whose agency alone these laws can be carried into execution have already resigned. We no longer have a district judge, a district attorney, or a marshal in South Carolina. In fact, the whole machinery of the Federal Government necessary for the distribution of remedial justice among the people has been demolished, and it would be difficult, if not impossible, to replace it.

The only acts of Congress on the statute book bearing upon this subject are those of February 28, 1795, and March 3, 1807. These authorize the President, after he shall have ascertained that the marshal, with his posse comitatus, is unable to execute civil or criminal process in any particular case, to call forth the militia and employ the Army and Navy to aid him in performing this service, having first by proclamation commanded the insurgents "to disperse and retire peaceably to their respective abodes within a limited time" This duty can not by possibility be performed in a State where no judicial authority exists to issue process, and where there is no marshal to execute it, and where, even if there were such an officer, the entire population would constitute one solid combination to resist him.

The bare enumeration of these provisions proves how inadequate they are without further legislation to overcome a united opposition in a single State, not to speak of other States who may place themselves in a similar attitude. Congress alone has power to decide whether the present laws can or can not be amended so as to carry out more effectually the objects of the Constitution.

SEC. 2. And be it further enacted, That whenever the laws of the United States shall be opposed, or the execution thereof obstructed, in any state, by combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings, or by the powers vested in the marshals by this act, it shall be lawful for the President of the United States, to call forth the militia of such state, or of any other state or states, as may be necessary to suppress such combinations, and to cause the laws to be duly executed; and the use of militia so to be called forth may be continued, if necessary, until the expiration of thirty days after the commencement of the then next session of Congress.

SEC. 3. Provided always, and be it further enacted, That whenever it may be necessary, in the judgment of the President, to use the military force hereby directed to be called forth, the President shall forthwith, by proclamation, command such insurgents to disperse, and retire peaceably to their respective abodes, within a limited time.

I mentioned that I'm re-reading Mills Thornton's Power and Politics in a Slave Society. If I weren't so lazy, I'd tell you how unfair my earlier semi-review of the book was. But since I am lazy, I'll content myself with my favorite quote so far. As you'll see, Professor Thornton does not think the south was ready for revolution in 1850. I enjoy the lines because Professor Thornton backs them up and because the first sentence is laugh-out-loud funny:

I mentioned that I'm re-reading Mills Thornton's Power and Politics in a Slave Society. If I weren't so lazy, I'd tell you how unfair my earlier semi-review of the book was. But since I am lazy, I'll content myself with my favorite quote so far. As you'll see, Professor Thornton does not think the south was ready for revolution in 1850. I enjoy the lines because Professor Thornton backs them up and because the first sentence is laugh-out-loud funny:It has been the fashion among some students of the Crisis of 1850 to pretend that a listener, if sufficiently attentive, can hear the thunder of the guns at Gettysburg in the debate over the Georgia Platform. The sounds which reach the present writer's ears, however, only emphasize that the decade which intervened between 1850 and 1860 was marked by the creation of very new social conditions, in Alabama as elsewhere. The electorate accepted in 1860 what it had rejected in 1850, not merely because affairs had taken a more serious turn at Washington but also because the voters were residents of a new world, which made new demands of them and to which they were compelled to offer new responses.

I was surfing the web with "CSI Miami" on in the background when I dimly heard the lead character, you know, the guy with red hair, say something like, "I'll tell you what. Let's keep this conversation between you and I."

I was surfing the web with "CSI Miami" on in the background when I dimly heard the lead character, you know, the guy with red hair, say something like, "I'll tell you what. Let's keep this conversation between you and I."

Voting [in pre-War Alabama] was by ballot, but a number was placed on each ballot corresponding to a number by the voter's name on the master list, so it was possible later to determine how each man had used his franchise.

Christopher C. Danley comes across in James M. Woods' Rebellion and Realignment: Arkansas's Road to Secession (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press 1987) as one of the more interesting figures in pre-War Arkansas. Danley assumed the editorship of the Whig Arkansas Gazette, based in Little Rock, in 1853. He became a Know Nothing, and the Gazette became the leading Know Nothing paper in the state.

Christopher C. Danley comes across in James M. Woods' Rebellion and Realignment: Arkansas's Road to Secession (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press 1987) as one of the more interesting figures in pre-War Arkansas. Danley assumed the editorship of the Whig Arkansas Gazette, based in Little Rock, in 1853. He became a Know Nothing, and the Gazette became the leading Know Nothing paper in the state.As a conservative, Danley believed an answer to the sectional crisis lay in economic, not political independence. The Gazette editor proposed that the South boycott Northern goods and develop Southern industry. He called for vigorous interstate trade among slaveholding states and more direct trade with England and Franc, which meant that the cotton South could bypass Yankee merchants and middlemen. If the South became economically and educationally independent of the North, Danley reasoned, it could then stay in the Union without having to worry about Northern attitudes and opinions. Far from being a disunionist, the Little Rock editor planned to keep the states united by having the Old South become more independent of the North.

Thanks to the anonymous commenter (commentor? commentater? commentator?) who, several months ago at least, recommended James Woods' Rebellion and Realignment: Arkansas'a Road to Secession. I'm less than half way through it but I'm enjoying tremendously.

Thanks to the anonymous commenter (commentor? commentater? commentator?) who, several months ago at least, recommended James Woods' Rebellion and Realignment: Arkansas'a Road to Secession. I'm less than half way through it but I'm enjoying tremendously. A British traveler had this to say about a state in the late 1830s:

A British traveler had this to say about a state in the late 1830s:Gentlemen who have taken the liberty to imitate the signature of other persons, bankrupts who were not disposed to be plundered by their creditors, homicides, horse stealers, and gamblers, all admired [the state in question] on account of the gentle and tolerant state of opinion which prevails there.

People at a distance easily come to the conclusion that [the state] is only famous for private brawls and lynchings, and the bloodiest encounters in the annals of border warfare. Consequently, a typical [citizen of the state] is pictured as a person in a semi-barbaric state, half-alligator, half-horse . . . armed to the teeth, bristling with knives and pistols, a rollicking, daredevil type of personage, made up of coarseness, ignorance, and bombast . . ..

measurably increased the difficulty of launching a third party . . .. Since those major parties had an automatic slot on the ballots governments prepared and since the legal hurdles for other parties to get on those ballots were so high, Republicans and Democrats effectively monopolized voters’ choices.

the rules of the political game encouraged rather than inhibited the creation of new parties. Instead of state-printed ballots that gave legally recognized major parties pride of place and disadvantaged other groups who sought to be listed on them, political parties printed their own ballots. As a result, it was far easier for new parties to challenge the old ones.

I have posted previously about Millard Fillmore and have made no bones about my belief that he was an admirable man and a fine president.

I have posted previously about Millard Fillmore and have made no bones about my belief that he was an admirable man and a fine president.