The trial judge of the Parish Court, for the Parish and City of New Orleans, clearly disliked the state of slave freedom law in Louisiana. In particular, he was unhappy with the Supreme Court of Louisiana's ruling in Marie Louise v. Marot (1836), in which the court had held that "there is no slavery permitted in France; that, as soon as a slave lands on French soild, he is free by the mere fact." (I have previously posted on Marie Louise v. Marot. To read those post, click on the label at the right.)

The trial judge of the Parish Court, for the Parish and City of New Orleans, clearly disliked the state of slave freedom law in Louisiana. In particular, he was unhappy with the Supreme Court of Louisiana's ruling in Marie Louise v. Marot (1836), in which the court had held that "there is no slavery permitted in France; that, as soon as a slave lands on French soild, he is free by the mere fact." (I have previously posted on Marie Louise v. Marot. To read those post, click on the label at the right.)In effect, the Parish Court judge sought to persuade the Supreme Court to change its mind:

The judge of the Parish Court has admitted, that if the decision of this court, in the case of Marie Louise, be correct, it affords a legitimate rule by which the present case is to be determined; but he contends that a single decision of this court does not prevent the reexamination of the principle recognized when it comes up a second time, and is presented to the consideration of the court.

The Supreme Court archly noted that Marie Louise was "not the first [case] in which" it had "been called upon to revise the judgment of an inferior court" on the issue of slave freedom. To begin with, "[a]bout fifteen years ago, the court of the third judicial district [had] recognize[d] the right to freedom of a slave, carried from Kentucky into the state of Ohio by her former owner," and the Louisiana Supreme Court affirmed. Even in that case "[t]he question was not res nova in the jurisprudence of these states; the plaintiff [slave] relied on a decision of the Court of Appeals of the state of Kentucky, which fully supported her claim."

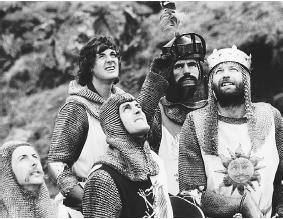

Ten years later, the Supreme Court of Louisiana reaffirmed its decision. Thus, Marie Louise was the third, not the first pronouncement by the Supreme Court on the issue. Even so, the Supreme Court said, it was willing to consider the issue once more. Read the following passage aloud, using a fake French accent and dripping with sarcasm a la Monty Python in "The Holy Grail:"

We agree with our learned brother in the Parish Court, that "more than one decision of the supreme judicial tribunal is required to settle the jurisprudence on any given point or question of law;" and accordingly, as there has been three decisions of this court on the question on which he differs from us, we might consider the law as settled by these repeated decisions, in which all the members of the court concurred, and which were in accordance with three judgments of the District Courts; nevertheless, we have attended to the new considerations which have been submitted to us.

In the next post, I'll review the "new considerations" that were "submitted to" the Supreme Court of Louisiana, and that court's responses.

No comments:

Post a Comment