Since I've been on a mini Christopher Hitchens kick, try his brutal trashing of George Tenet: "A Loser's History: George Tenet's Sniveling, Self-Justifying Book Is a Disgrace".

Booknotes: Death or Victory

1 day ago

History (Mostly Antebellum America), Law, Music (from Classical to Frank Zappa -- are they the same?) and More

The [Louisiana] Democrats concentrated their venom on Whig vice presidential candidate Millard Fillmore. Arguing that northern Whigs were antagonistic to slavery and had voted in favor of the Wilmot Proviso, Democrats reminded voters that they could not vote for Taylor without voting for the "avowed and notorious abolitionist" Fillmore. Democratic orators denied they slandered Fillmore with this designation because they claimed to possess evidence that Fillmore had proudly called himself an abolitionist.

I am honored by the receipt of your note the 21st ult. [i.e., October 21, 1848], enclosing a copy of the address of the "Fillmore Rangers" of New Orleans.

It did not reach me until the contest had closed, and the din of strife had given way to the exultations of triumph and the song of victory.

But I can assure you that the noble and truly national sentiments of that address find a hearty response in my breast, and the triumphant Whig vote in your city is the best evidence of the zeal and ability with which the young men of your club discharge their duty to the Whig party and the country. My illustrious associate on the ticket required no vindication, and I therefore feel the more deeply the obligation which I have incurred by the noble stand which these young men took in my favor, and I acknowledge it with heartfelt thanks, and trust they will never have reason to regret the confidence they have reposed in me.

Please make my grateful acknowledgments to the Club over which you preside, and accept for yourself the assurance of my high regard and esteem.

Since I suddenly seem to be on a Thomas Jefferson kick . . .

Since I suddenly seem to be on a Thomas Jefferson kick . . .If then he is to be accused of seducing a sixteen-year-old slave girl and having children by her whom he held as slaves, it is in utter defiance of the testimony he bore over the course of a long lifetime of the primacy of the moral sense and his loathing of racial mixture. . . How can his frequent assertions that his conscience was clear and that his enemies did him a cruel and wholly unmerited injustice be reconciled with the Jefferson of the Sally Hemings story? -- unless, of course, Jefferson is set down as a practitioner of pharisaical holiness who loved to preach to others what he himself did not practice?

If the answer . . . is that Jefferson was simply trying to cover up his illicit relations . . . he deserves to be regarded as one of the most profligate liars and consummate hypocrites ever to occupy the presidency. To give credence to the Sally Hemings story is, in effect, to question the authenticity of Jefferson's faith in freedom, the rights of man, and the innate controlling faculty of reason and the sense of right and wrong. It is to infer that there were no principles to which he was inviolably committed, that what he acclaimed as morality was no more than a rhetorical facade for self-indulgence, and that he was always prepared to make exceptions in his own case when it suited his purpose. In short, beneath his sanctimonious and sententious exterior lay a thoroughly adaptive and amoral public figure . . ..

Since I just mentioned Christopher Hitchens's Jefferson biography, here are some thoughts I set down about the book while reading it:

Since I just mentioned Christopher Hitchens's Jefferson biography, here are some thoughts I set down about the book while reading it:Dumas Malone, Jefferson's most revered biographer, continued in this tone as late as 1985, writing that for Madison Hemings to claim descent from his master was no better than "the pedigree printed on the numerous stud-horse bills that can be seen posted around during the Spring season. No matter how scrubby the stock or whether the horse has any known pedigree, owners invented an exalted stock for their property." In other words, for many decades historians felt themselves able to discount [James] Callender's story because it had originated with a contemptible bigot who had a political agenda. But one cannot survey the steady denial, by a phalanx of historians, of the self-evident facts without appreciating that racism, sexism, and political partisanship have also been manifested in equally gross ways, and by more apparently 'objective' means, and at the very heart of our respectable academic culture.

The ever-refreshing Christopher Hitchens (whose brief biograph of Jefferson I enjoyed, although I wish it had been more acerbic) has an interesting article up at City Journal: "Jefferson Versus the Muslim Pirates". Here's a snippet:

The ever-refreshing Christopher Hitchens (whose brief biograph of Jefferson I enjoyed, although I wish it had been more acerbic) has an interesting article up at City Journal: "Jefferson Versus the Muslim Pirates". Here's a snippet:How many know that perhaps 1.5 million Europeans and Americans were enslaved in Islamic North Africa between 1530 and 1780? . . .

Some of this activity was hostage trading and ransom farming rather than the more labor-intensive horror of the Atlantic trade and the Middle Passage, but it exerted a huge effect on the imagination of the time—and probably on no one more than on Thomas Jefferson. Peering at the paragraph denouncing the American slave trade in his original draft of the Declaration of Independence, later excised, I noticed for the first time that it sarcastically condemned “the Christian King of Great Britain” for engaging in “this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers.” The allusion to Barbary practice seemed inescapable.

I'm a few days late, but 145 years ago last week (April 16, 1862) President Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, ending slavery in the District. The Act provided for the immediate emancipation of the District's slaves and compensation to loyal Unionist masters. Compensation was limited to no more than $300 for each slave and $1MM in total.

I'm a few days late, but 145 years ago last week (April 16, 1862) President Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, ending slavery in the District. The Act provided for the immediate emancipation of the District's slaves and compensation to loyal Unionist masters. Compensation was limited to no more than $300 for each slave and $1MM in total.No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

All those stupid history books claim that the American (aka Know Nothing) party died c. 1857. It turns out they're all wrong. Michael Novak at NRO points out that the KNs are doing just fine.

All those stupid history books claim that the American (aka Know Nothing) party died c. 1857. It turns out they're all wrong. Michael Novak at NRO points out that the KNs are doing just fine.As slave prices fell and receded in prominence, Southern vulnerability to rhetorical attacks might have diminished as well. If this analysis is correct, then the missed opportunities for delay and compromise during 1859-61 loom larger and larger historically. But as difficult as the proposition is for twentieth-century Americans to accept, it was slavery as well as the Union that would have been preserved for a long time. Slavery would have faced internal political and economic pressures in the South, but the notion that slavery would have faded away peacefully in the late nineteenth century has always been a wishful chapter in historical fiction, not part of a plausible counterfactual history.

Such a financial asset involves external effects of region-wide scope: even if I attach no importance whatsoever to fugitive slave legislation as it effects [sic] my own slaves, if I think that you (any nontrivial number of slaveowners or buyers) attach some importance to it, then the issue affects me financially and I have good reason to become a political advocate of strong guarantees.

The closest analogy today is the behavior of homeowners. A house is typically the largest asset owned by a family -- indeed families are usually heavily in debt if they buy a house -- and here also the value of the property depends on the opinions and prejudices of others. In this case as well, prejudice and intolerance are intensified by market forces. I may not really care whether a black family moves next door, but, if I feel that others care, I will be under financial pressure to share their views or at least act as though I do. The main difference between the housing case and slavery are that many owners held more than one slave, and that for slavery these were not "neighborhood effects" limited to a small geographic area but system-wide externalities, so that a threat to slavery anywhere was a threat to slaveowners everywhere. The effect was to greatly exacerbate the response to any threat.

The strength of the argument is that it is not based on an exclusively economic nor exclusively rational conception of motivation and behavior. Fear, racism, misperceptions, and long-run strategic calculations all undoubtedly did exist. The point is that economic forces served to intensify every other motive for the South's insistence on guarantees of the rights of slaveholders and even the quest for a virtual endorsement of slavery by the North. The argument does not imply that Southern politicians were scrutinizing slave prices in their every action; but the widespread concern over property values created a situation in which an ambitious politician could easily mobilize a constituency by strongly insisting on absolute guarantees for slaveowners' rights.

There is no doubt in my mind that Michael Holt's The Political Crisis of the 1850s is one of the most important books written about the causes of the Civil War in the past thirty years. In it, Professor Holt posits that any theory about why the south seceded must explain why the seven lower southern States seceded based merely on President Lincoln's election, while the remaining slaveowning States did not do so.

There is no doubt in my mind that Michael Holt's The Political Crisis of the 1850s is one of the most important books written about the causes of the Civil War in the past thirty years. In it, Professor Holt posits that any theory about why the south seceded must explain why the seven lower southern States seceded based merely on President Lincoln's election, while the remaining slaveowning States did not do so.A solid South [in favor of secession] would have to transcend the social fact that 47 percent of the Lower South's peoples were slaves compared to 32 percent of the Middle South's and 13 percent of the Border South's, the political fact that that ex-Whigs (later Americans or Know-Nothings and yet later Oppositionists and still later Constitutional Unionists) had remained very competitive in the Upper South while becoming largely unelectable in the Lower South, and the later electoral fact that John Breckenridge had received 56 percent of the Lower South's 1860 popular presidential vote compared to 32 percent in the Border South.

Lowly whites as black belt political superiors had no qualms about elevating squires to the legislature or about ousting abolitionists from the neighborhood. In the paramilitary societies that patrolled the lowcounty in the fall of 1860, nonslaveholders paraded beside their richer neighbors, proudly keeping blacks ground under. The patriarchal obligation of all white men to guard their wives, gratifying to poor men's chauvinistic egos, included the necessity to keep a 90 percent black majority from murdering white dependents.

This may be a better (or worse) guess than Stephanie McCurry's speculation that white yeomen massed behind wealthier men's domination over dependent blacks in order to preserve white males' domination over dependent wives. We are all guessing from missing evidence about yeomen's motives; that is usually a difficulty with history from the bottom up. But I've seen no hint that South Carolina white males feared, or had the slightest reason to fear, female domination before the war. In contrast, I've seen much evidence that fear of racial unrest afflicted lowcountry whites -- and plenty of reason for that fear. Still, Professor McCurry's gender-based speculation is intriguing; her evidence of poorer whites' full participation in 1860 paramilitary pressures is irrefutable; and I applaud her success in making the hitherto invisible lowcountry white nonslaveholders highly visible in the secession story. . ..

Over at Civil War Memory, Kevin Levin is mystified as to why Don Imus felt free to use the phrase "nappy-headed hos" on his show:

Over at Civil War Memory, Kevin Levin is mystified as to why Don Imus felt free to use the phrase "nappy-headed hos" on his show:What I don't understand is why as a society we continue to tolerate this kind of language. Don Imus has one of the most popular radio talk shows (broadcasted [sic] live on MSNBC) and is a regular stop for politicians on the campaign trail, well-regarded journalists, and other popular figures. What I have difficulty understanding is the fact that he apparently felt comfortable enough to say those things at all. There was no hesitation in sharing these thoughts over the wires owned by NBC.

Let's stipulate: I have no love for Don Imus, Al Sharpton, or Jesse Jackson. I repeat: A pox on all their race-baiting houses.

Let's also stipulate: The Rutgers women's basketball team didn't deserve to be disrespected as "nappy-headed hos." No woman deserves that. I agree with the athletes that Imus's misogynist mockery was "deplorable, despicable and unconscionable." And as I noted on Fox News's O'Reilly Factor this week, I believe top public officials and journalists who have appeared on Imus's show should take responsibility for enabling Imus—and should disavow his longstanding invective.

But let's take a breath now and look around. Is the Sharpton & Jackson Circus truly committed to cleaning up cultural pollution that demeans women and perpetuates racial epithets? Have you seen the Billboard Hot Rap Tracks chart this week?

An "Event Release" by NYU touting a conference entitled "Alger Hiss and History" seems to suggest that significant questions remain concerning Hiss's guilt:

An "Event Release" by NYU touting a conference entitled "Alger Hiss and History" seems to suggest that significant questions remain concerning Hiss's guilt:The 1948 Alger Hiss case was a major moment in post-World War II America that reinforced Cold War ideology and accelerated America’s late-1940’s turn to the right. When Hiss, one of the nation’s more visible New Dealers, was accused of spying for the Soviet Union and convicted of perjury, his case was seen as one of the most significant trials of the 20th century, helping to discredit the New Deal, legitimize the red scare, and set the stage for the rise of Joseph McCarthy.

As scholars have gained access to the archives in the former Soviet Union and more U.S. documents have been declassified, there has been renewed debate about the Hiss case itself and the larger issues of repression, civil liberties, and internal security that many believe speak to current public policy and discussions.

Michael Holt has argued that the lower south promptly seceded after Lincoln's election while the middle and upper south did not because, among other things, the lower south had never developed a viable two-party system. Cotton south Democrats thus lacked the experience of falling out of power and then rallying and coming back in the next election. When Lincoln won in 1860, they did not see it as a potentially temporary setback, to be overcome by normal democratic processes, but rather the beginning of permanent minority.

Michael Holt has argued that the lower south promptly seceded after Lincoln's election while the middle and upper south did not because, among other things, the lower south had never developed a viable two-party system. Cotton south Democrats thus lacked the experience of falling out of power and then rallying and coming back in the next election. When Lincoln won in 1860, they did not see it as a potentially temporary setback, to be overcome by normal democratic processes, but rather the beginning of permanent minority.Thus where the heavily enslaved Lower South's experience with nativism [the American Party in 1854-56] had yielded a largely one-party system, with the hapless ex-Whig remnant in position only to carp at the proslavery Democracy, the lightly-enslaved Border South had regenerated a competitive two-party system, with the powerful ex-Whig fragment in position to defeat the Democracy. The Lower South and Border South had generated different political institutions, compounding their different social institutions. In 1860, the borderland's powerful surviving ex-Whig partisan organizations would give the region's Unionist Party a leg up in defeating secessionists. But in the Lower South, the uncompetitive ex-Whigs would offer no such institutional bulwark against disunion.

[The westward expansion of the cotton belt], from inferior to superior soil, has given rise to greatly exaggerated conceptions of the extent of soil exhaustion and erosion in the Southeast. Cotton is not in fact a highly exhaustive crop, and the gutted, windswept hills of the Piedmont, so vividly described by Olmstead and De Bow, were as much the result of abandonment as its cause.

I am wending my way through William Freehling's Road to Secession Volume II. After about 150 pages, my reaction is that this should not be the first book you should read on the period 1854-1861. Professor Freehling is too idiosyncratic a writer for that. Putting aside his offputting writing style, the good professor tends to zero in on particular topics that interest him -- for example, the tensions inherent in different southern justifications of slavery -- and then gives comparatively brief treatment to others.

I am wending my way through William Freehling's Road to Secession Volume II. After about 150 pages, my reaction is that this should not be the first book you should read on the period 1854-1861. Professor Freehling is too idiosyncratic a writer for that. Putting aside his offputting writing style, the good professor tends to zero in on particular topics that interest him -- for example, the tensions inherent in different southern justifications of slavery -- and then gives comparatively brief treatment to others. I really like Herodotus. He seems like a guy you would have wanted to have over for a dinner party. Give him a good meal, a couple of kraters of wine, and get him talking.

I really like Herodotus. He seems like a guy you would have wanted to have over for a dinner party. Give him a good meal, a couple of kraters of wine, and get him talking.Geneticists have added an edge to a 2,500-year-old debate over the origin of the Etruscans, a people whose brilliant and mysterious civilization dominated northwestern Italy for centuries until the rise of the Roman republic in 510 B.C. Several new findings support a view held by the ancient Greek historian Herodotus — but unpopular among archaeologists — that the Etruscans originally migrated to Italy from the Near East.

* * *

An even more specific link to the Near East is a short statement by Herodotus that the Etruscans emigrated from Lydia, a region on the eastern coast of ancient Turkey. After an 18-year famine in Lydia, Herodotus reports, the king dispatched half the population to look for a better life elsewhere. Under the leadership of his son Tyrrhenus, the emigrating Lydians built ships, loaded all the stores they needed, and sailed from Smyrna (now the Turkish port of Izmir) until reaching Umbria in Italy.

Despite the specificity of Herodotus’ account, archaeologists have long been skeptical of it. There are also fanciful elements in Herodotus’ story, like the Lydians’ being the inventors of games like dice because they needed distractions to take their minds off the famine. And Lydian, unlike Etruscan, is definitely an Indo-European language. Other ancient historians entered the debate. Thucydides favored a Near Eastern provenance, but Dionysius of Halicarnassus declared the Etruscans native to Italy.

* * *

With the geneticists in disarray, archaeologists had been able to dismiss their results. But a new set of genetic studies being reported seems likely to lend greater credence to Herodotus’ long-disputed account.

Three new and independent sources of genetic data all point to the conclusion that Etruscan culture was imported to Italy from somewhere in the Near East.

* * *

As for Herodotus, Ms. Jovino said she believed, liked most modern historians, “that he does not always report real historical facts.” often referring to oral tradition.

But at least on the matter of Etruscan origins, it seems that Herodotus may yet enjoy the last laugh.

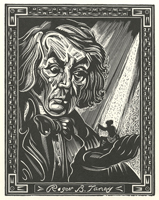

Why does this seem to place Chief Justice Taney in such a different light? At the same time he was declaring that blacks were not, and never could be, citizens:

Why does this seem to place Chief Justice Taney in such a different light? At the same time he was declaring that blacks were not, and never could be, citizens:Roger B. Taney gradually manumitted almost all of [his] slaves. None of his liberated slaves, wrote . . . Taney at the time of his . . . Dred Scott Decision, "have disappointed my expectations . . . They were worthy of freedom; and knew how to use it."

Brzezinski said there's no reason to think a bloodbath would necessarily follow a U.S. withdrawal.

"We expected that the U.S. leaving Vietnam would result in massive killings and genocide and so forth, and collapse of the dominoes in Southeast Asia," he said. "It didn't happen. How certain are we of the horror scenarios that have been mentioned in what will take place in Iraq?"

Earlier this year, I published a number of posts concerning the New York Court of Appeals decision in Lemmon v. People (1860), in which the court held that even the transitory presence of a slave in the State of New York made the slave free. (You can find those posts by clicking on the "Lemmon v. People" link at the right.) At the time, Republicans expressed concern that the Supreme Court of the United States might use the case, or another like it, as a vehicle to extend the Dred Scott decision by holding that free states could not constitutionally bar or free slaves brought into those states by their masters.

Earlier this year, I published a number of posts concerning the New York Court of Appeals decision in Lemmon v. People (1860), in which the court held that even the transitory presence of a slave in the State of New York made the slave free. (You can find those posts by clicking on the "Lemmon v. People" link at the right.) At the time, Republicans expressed concern that the Supreme Court of the United States might use the case, or another like it, as a vehicle to extend the Dred Scott decision by holding that free states could not constitutionally bar or free slaves brought into those states by their masters.The question recurs, what will satisfy them [the southern people]? Simply this: We must not only let them alone, but we must somehow, convince them that we do let them alone. This, we know by experience, is no easy task. We have been so trying to convince them from the very beginning of our organization, but with no success. In all our platforms and speeches we have constantly protested our purpose to let them alone; but this has had no tendency to convince them. Alike unavailing to convince them, is the fact that they have never detected a man of us in any attempt to disturb them.

These natural, and apparently adequate means all failing, what will convince them? This, and this only: cease to call slavery wrong, and join them in calling it right. And this must be done thoroughly - done in acts as well as in words. Silence will not be tolerated - we must place ourselves avowedly with them. Senator Douglas' new sedition law must be enacted and enforced, suppressing all declarations that slavery is wrong, whether made in politics, in presses, in pulpits, or in private. We must arrest and return their fugitive slaves with greedy pleasure. We must pull down our Free State constitutions. The whole atmosphere must be disinfected from all taint of opposition to slavery, before they will cease to believe that all their troubles proceed from us.

I am quite aware they do not state their case precisely in this way. Most of them would probably say to us, "Let us alone, do nothing to us, and say what you please about slavery." But we do let them alone - have never disturbed them - so that, after all, it is what we say, which dissatisfies them. They will continue to accuse us of doing, until we cease saying.

I am also aware they have not, as yet, in terms, demanded the overthrow of our Free-State Constitutions. Yet those Constitutions declare the wrong of slavery, with more solemn emphasis, than do all other sayings against it; and when all these other sayings shall have been silenced, the overthrow of these Constitutions will be demanded, and nothing be left to resist the demand. It is nothing to the contrary, that they do not demand the whole of this just now. Demanding what they do, and for the reason they do, they can voluntarily stop nowhere short of this consummation. Holding, as they do, that slavery is morally right, and socially elevating, they cannot cease to demand a full national recognition of it, as a legal right, and a social blessing.

By the general law of nations, no nation is bound to recognise the state of slavery, as to foreign slaves found within its territorial dominions, when it is in opposition to its own policy and institutions, in favor of the subjects of other nations where slavery is recognised. If it does it, it is as a matter of comity, and not as a matter of international right. The state of slavery is deemed to be a mere municipal regulation, founded upon and limited to the range of the territorial laws. This was fully recognised in Somerset's Case, . . . decided before the American revolution. It is manifest, from this consideration, that if the constitution had not contained this clause [the Fugitive Slave Clause], every non-slave-holding state in the Union would have been at liberty to have declared free all runaway slaves coming within its limits, and to have given them entire immunity and protection against the claims of their masters; a course which would have created the most bitter animosities, and engendered perpetual strife between the different states. The clause was, therefore, of the last importance to the safety and security of the southern states, and could not have been surrendered by them, without endangering their whole property in slaves. The clause was accordingly adopted into the constitution, by the unanimous consent of the framers of it; a proof at once of its intrinsic and practical necessity.